Originally published in AutoWeek February 1, 1982

Alexander Winton in the Winton Bullet No. 2; Contemporary photograph, public domain

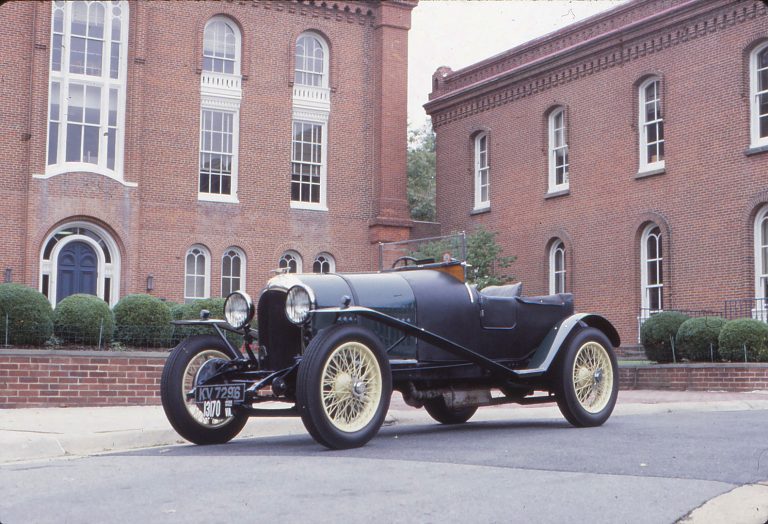

It was…unexpected. The hood is broad and flat behind the wedge-shaped nose. Low and clean lined, it looks almost modern. Such appearances, though, are betrayed by the tall wheels, narrow tread and the exposed driving position. It is, nonetheless, a stunningly handsome machine.

It was the zenith of Alexander Winton’s racing endeavors, the Bullet No.2, and it is as remarkable for its ingenuity of design as it is for its good looks. It was turned-of-the-century high-tech, but it was caught between the woof and the warp of horseless carriage methods and true automotive design.

Unlike what was so often the case in those early days—only a decade had passed since the Durayea brothers built this country’s first car in their second-story shop—the Winton Bullet No. 2 was built as a racer from the ground up. Many of its 1903 peers were converted passenger cars, but not the Bullet.

The huge engine is literally the center of the car, both in concept and construction. It is a great thumping power mill, a straight eight of 1,029 cubic inch displacement. Huge coffee cans of pistons sweep through a bore and stroke a 5.25 and 6 inches respectively. The cylinders of the mighty engine are horizontal, allowing for the unusually low profile of the racer. Remarked a contemporary report in Horseless Age, “the center of gravity is extremely low and the flywheel has but six to seven inches road clearance.”

The massive eight is actually two fours bolted together. There are two aluminum crankcases, each with its own four-cylinder block. Twin crankshafts bolt together in the space between the two crankcases, as do the two camshafts. Under each block is an aluminum centrifugal water pump, driven off a single shaft running back from the aluminum timing cover at the front of the engine. The water jackets of the two blocks are also of aluminum, as are the water manifolds.

The camshafts have lobes only for the overhead-type exhaust valves. The intake valves are “automatic,” that is, intake stroke actuated. Winton was unique in his method of vehicle speed control. Whereas earlier method included constant speed engines with vehicle speed selected only by gearing, or lowering engine speed by lifting exhaust valves off the seats, and the trend was toward throttled carburetors. Winton devised a system to control power output with the intake valves.

An air pump, secured to the outside of the first block and operated by a rod connected to the skirt of the third piston, supplies compressed air to small pistons on the ends of the eight intake valves through a maze of tubing. The compressed air acts against the suction of the intake stroke which pulls the intake valve open. Thus, pressure from the pump keeps effective lift low. That limits the intake charge and thereby the power and speed of the engine. The driver can bleed off air pressure with either a hand valve or a foot plunger. With less pressure on the piston over the intake valve, the valve open further. A greater intake charge can enter, thus allowing more power and speed.

Call it either a valve-throttle engine or a variable “camshaft,” but don’t call it untested. Winton had used the system on this car’s predecessor, the vertical four-powered Bullet No. One, the first car to cross the North American continent. A 1903 Winton also use the system. Even as with today’s racers, the Bullet No. 2 uses varying carburetion, a single carb at first and later one per block.

Ignition is by spark from eight coils under the seat energized by a battery. The car has neither a magneto or charging system. The low-tension ignition timer is advanced and retarded by a small lever at the drivers seat.

The radiator is equally massive as the engine. Cast-aluminum header plates bracket 42 horizontal tubes in a seven-by-six arrangement, each tube carrying dozens of cooling discs. Coolant passes from the upper right of the radiator to the lower left, then to the pumps and into the lower water jackets and out of the upper. Water manifolds then carry the water back to the radiator.

Attached to either side of the engine is a two-inch thick by 3.5-inch high wooden rail which, along with a wooden cross member at front and rear, comprises the frame. One suspects, though, that the giant engine is the main “frame member,” not the relatively small pieces of wood. The body, i.e., the cover over the hood and the tall section, also is wood, and has overhead inspection doors. Two bucket seats are mounted on the body, well towards the rear of the Bullet, but with the feet of the occupants centered over the rear half of the engine. There is no floor; the engine is fully visible from the driver’s seat.

The aluminum-hubbed-and-spoked steering wheel seems to be mounted rather for forward, a goodly distance from the driver. Considering how the driver would have to lean into an 80 mile-per-hour wind, the placement appears to be just right for chest-down bent-arm muscling.

At each corner is a 34-inch wooden-spoke wheel mounted with five-inch wide tires, undamped except for friction, and semi-elliptic springs front and rear. The front springs carry a solid steel forging with a kick up at each end where the spindles are located. A four-foot long drag link connects to the Pitman arm of the aluminum housing containing warm and sector steering gear.

The rear axle is live, with a bronze differential housing and tubular steel axle housings. Axle location is by the spring and radius rods connected to the sides of the frame, and by two parallel torque arms to the rear crossmember. A divided trust rod helps support the differential.

There is no transmission in the modern sense. Forward is by direct drive only, with the differential ratio of approximately 1.25:1. An internal expanding-shoe-type clutch connects the flywheel to a large metal gear-toothed disk, which is then linked to the differential by a short drive shaft with two universal joints. The gear-toothed disk is part of the reversing “system,” for which power is taken off the front of the engine to a collection of gears and shafts and run back to the disk. The driver had to manipulate three levers whenever he wanted to back up, making testers of modern cars complaints about “where reverse should be” seem like petty carping.

In forward drive the, the tall wheels and long gears would produce 64 mph at 700 RPM. At the engine’s maximum of 1000 thudding RPM, top speed was calculated to be 90 mph.

The whole package weighs in at 2150 pounds, heavier than the 1900 pounds Winton had planned, but within the 2200 pounds (1000 kg) class with a few pounds to spare. This weight—in fact the entire effort—is remarkable, a product of the wild and unfettered competition of the infant auto industry.

Alexander Winton was a believer in the concept of “win on Sunday, sell on Monday,” an idea which had considerable validity in an age when automobile and automobile racing captured even more of the public psyche than it does today. Winton was a builder of quality automobiles and sought to prove it by racing. The Bullet No. 1 had lost to Henry Ford’s famous 999 in sheer speed in a race over a frozen Michigan lake, so Winton sought to recapture the world’s attention by winning the 1903 Gordon Bennett road race, described by the contemporary press as the automotive equivalent of yachting’s America’s Cup. It was for this purpose that the Bullet No, 2 was built.

How well it would have performed will never be known. At the very start of the race, the throbbing of the mighty engine fell silent. Bad gasoline, contaminated with paraffin [kerosene], had “stopped up the spraying nozzle of his carburetor.” Lost were 48 minutes in determining the cause and fixing it. Lost also was a race. Winton gave chase, but surrendered before long against impossible odds. The greatly desired attention was focused not on Winton the Victor, but Winton the non-running competitor.

The only valor the Bullet No. 2 two was able to recoup for Winton was to bound the Daytona sands at 83.7 mph in the winter of 1904. It was “very close to the world’s record.” The rapid development of automotive technology was leaving the Bullet out-classed for international competition, so rather than enter it in unwinnable competition, Winton sold the Bullet to Barney Oldfield to tour the country ignominiously as a dirt track match race workhorse.

Today, the Bullet No. 2 rests in the marble halls of the Smithsonian institution. Thousands pause to look and comment on its beauty, more than ever saw it race. More than ever saw its red and gold flashing through the dust. More than ever heard what must have been a marvelous, thundering sound, a precision cannonade exploding through the cavernous exhaust tubing.

Race again it never shall. Its carburetion and parts of its ignition are missing, and it’s a mechanical cripple. It is a glory that is passed, and shall never be again.

While the Winton Bullet No. 2 is still in the Smithsonian collection, it is currently not on exhibition.

The car is streamlined but it’s like the driver is sitting on the roof. As fast as the car will go, it must have been a trip trying to hang on.