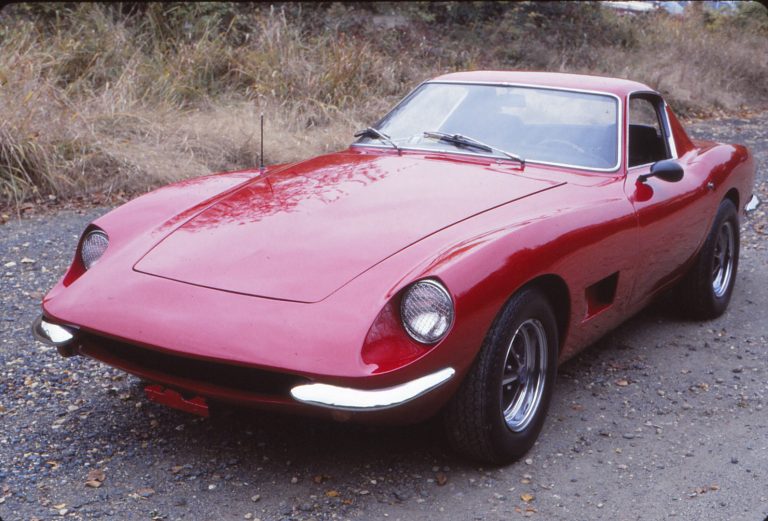

Eager and alert and minus only wings, tail structure and propeller, this Saab 96 resembles a stunt plane, striking in brilliant red paint, contours rounded and aerodynamic, fat tires stuffed into spat-like fenders.

The analogy goes beyond external appearances: The doors are light and the interior spare and close. The controls, of course, are automotive, but there’s no waste, no extra weight. Just standard gauges and a steering-column tachometer. Start the engine. The V4’s snarl is crisp and, with minimal sound insulation, right in your lap. This is not a typical Saab 96. Not that the 96 was, or is, particularly lacking. Ahead of its time in many ways, it was a direct descendent of the pioneering Saab 92, the car that started it all for the manufacture of military aircraft that added automobiles to its production after WW II.

History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek July 22, 1991; republished by author John Matras.

The 92, in addition to the two-stroke, two-cylinder engine, had front-wheel-drive and a drag coefficient of just over 0.32 when automotive aerodynamics generally meant looking like an airplane. Being slippery was important because the early Saabs were always less powerful than the competition in international rallying. “You couldn’t let up – ever,” later admitted Saab rally ace Eric Carlsson, nicknamed “On-the-roof” for some of his more, um, enthusiastic antics in 90-series Saabs.

Adding another cylinder to the two-stroke boosted power, but the 51-cid engine was pressed to produce 80 hp even in racing trim, and that with a very narrow rev range. Although a number of alternatives were considered – even a home-grown two-stroke V4 – Saab finally settled on the Ford four-stroke V4 originally intended for the ill-fated Cardinal project and used in the German-built Taunus.

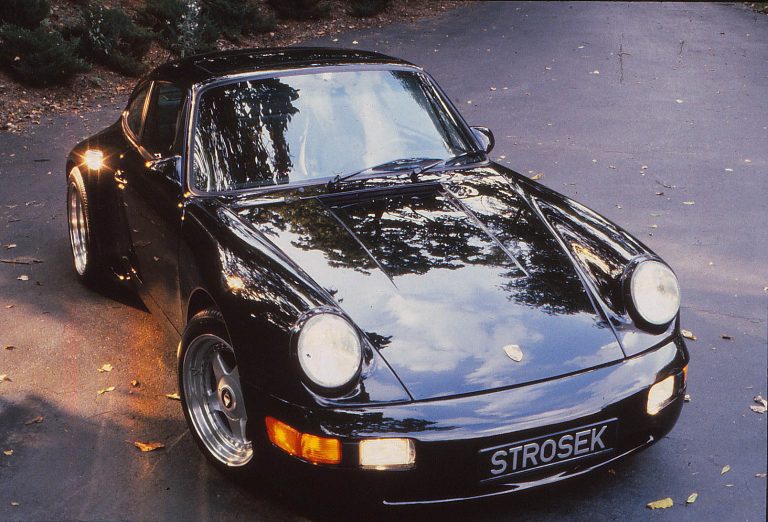

The Saab 96 V4 was introduced as a 1967 model. Saab had already faced the engine in competition and in the hands of Ford tuners, the 1.5-liter had been bumped to about 90 hp in race trim (up from 65 hp stock). Saab engineers fiddled with the engine and found another 25 hp, but found the engine strangling on the single two-barrel carb. The U.S. version of the engine, with a 106 cid displacement, brought power up to 125 hp in 1969 when race-modified. But in contrast with the Porsche 911, even that wasn’t enough. The final solution was a crossflow intake manifold devised in Saab’ s Competition Department in 1971.

With runners that interlaced over the Vee, the manifold allowed the use of side draft twin-throat Weber 45DCOE carburetors and provided an instant jump to 145 hp. A new head with separate exhaust ports gave another 15 hp in 1973, and when the new, better-handling Saab 99 replaced the 96 as the factory rally mount, the Competition Department was pulling 165 forces from the little V4!

Saabs have changed greatly since those days, the plush and powerful 9000 Turbo a prime example. Yet the 96 has a rough-hewn honesty that’s endearing, particularly when it’s muscled up per the Saab Competition Department. As did most manufacturers at the time, Saab made its speed parts available to the general public after development and use by factory teams.

Competition successes by independents are free advertising and anyway, they need to homologate the stuff. Saab kept an inventory of tuning kits and complete sport and race-tuned V4 engines even after production of the 96 ceased. Full of pictures of shiny crankshafts and glistening cylinder heads arrayed like cold-cuts on a party platter, the Saab Sports and Rally catalog was better than a Christmas wishbook. It offered parts like those of the ‘72 Saab 96 built by Andy Bittenbinder.

In addition to the array of Webers, the engine, which was balanced, has big valve heads with “split ports” in which a flange is added to de-siamese the exhaust port, forged pistons, Bosch racing distributor and special exhaust.

It rests on solid “Mexico” engine mounts – so named for Saab’s efforts in Baja. An oil cooler was fitted and the left headlight bezel drilled to allow more air to reach it. And even if it doesn’t, it gives the front end a more serious look. Final drive has been lowered to 5.431:1 (which makes you feel like a real hero if you take the non-corrected speedo seriously).

Pirelli P8 185/65-15’s are mounted on Saab Minilite-look wheels; there are also Sport & Rally springs and anti-rollbars. Bittenbinder sold the car, which won best in show at the Saab Club of North America’s 1990 national convention, to Len Schrader, co-owner of ReinersenMotors, a Denville, New Jersey, Saab dealership.

On the mountain roads of Eastern Pennsylvania Schrader’s Saab 96 Sport & Rally proved its mettle, streaking Porsche Guards Red through dips, twists and hollows, chased by the distinctive cadence of the V4’s exhaust, and biting into turns with trigger-happy abandon. There’s surprisingly little torque steer and the most difficult part is remembering the four-speed shifter is column-mounted. Put the Tripmaster in overdrive. We’re rally champs for sure. Looks like a stunt plane? Boogaloos like one too. ‘Cept for the barrel rolls. We’ll leave those to Carlsson.

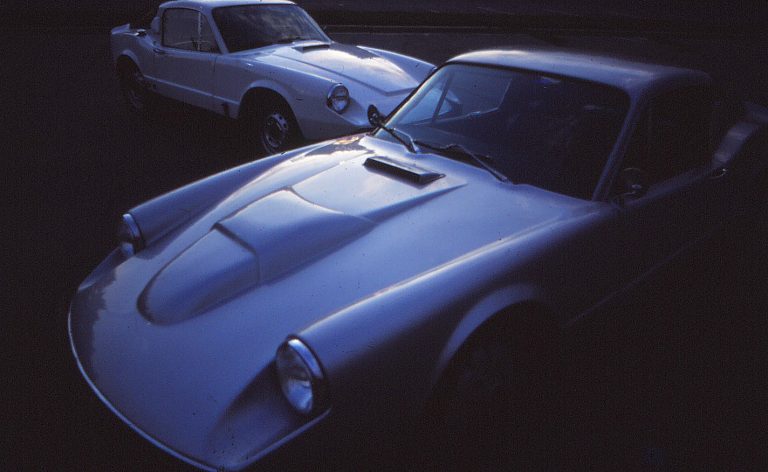

Addendum: Placing a modified V-4 under the hood of a Saab 96 Sport & Rally isn’t the only way to make a Saab 96 fo faster. Saab went all out with the Saab The Monster, a remarkable six-cylinder two-stroke car built for road racing, particularly taking on the Porsche 356.