History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek July 18, 1994.

The hood is narrow, much more so from the driver’s seat them when viewed from outside. The edges are emphasized by the slim fender ridges, sharp as exclamation points. The passenger sits only an elbow’s nudge away. This, for a 1976 model, seems like an old car. But then it is. The Triumph TR6 has a heritage, a legacy or – if you well – a burden dating back to the TR2. And while the gutsy TR2 blew the suicide doors clean off an MG-TD, by the 1976 model year the TR6 was competing with the likes of the Datsun Z and TR7.

The TR6 was the final incarnation of the trusty if musty design. Debuting in the 1969 model year, the TR6 continued with the 2.5-liter in-line six that had turned the TR4 into the TR250. But to freshen the aging Michelotti the styling of the 4-series Triumphs, Leyland turned to Karmann of Osnabruk, the West German firm well-known for its work for Volkswagen, Porsche and BMW. Michelotti had been unavailable – busy on another project for Leyland – but the British firm could not have hoped for better results.

History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek July 18, 1994, republished by author John Matras.

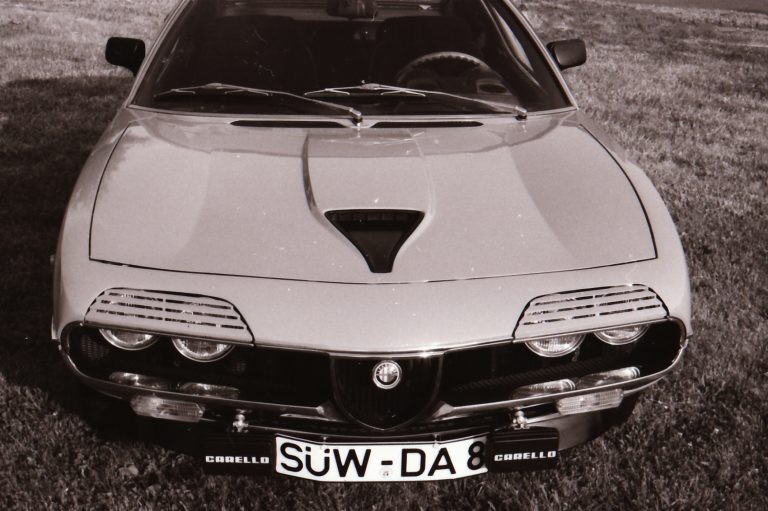

Karmann gave the sports car what has been called a Kal Kustom treatment, removing excess and simplifying the design. The front-with-eyelids headlamps of the TR for were integrated into the front fenders of the TR6 and the hood was shaved. A new single-bar grille replaced a busier predecessor. The tail was given a neat Kamm-style chop – though undoubtedly to negligible aerodynamic effect. Yet the hard points and center section were unchanged. It was a new look for relatively few pound sterling.

The chassis was unchanged, saving even more development costs, keeping the double A-arm front suspension and independent semitrailing-arm rear layout inherited from the TR4A. Yet the big, old pushrod six is mounted well back in the chassis, giving an almost ideal 51/49 front-to-rear weight distribution. But that didn’t yield phenomenal skidpad figures. Shod with 185/15 radials, the TR6’s 0.68g lateral grip was less than some contemporary sedans of not particularly sporting configuration. However, the engine setback did steal some room from the passenger compartment.

Thus the Triumph TR6 feels even older than the 1976 model year suggests.

On the other hand, this particular Triumph TR6, owned and restored by Bob Lear of Stroudsburg, Pa., comes to life with a guttural snarl. The six has always had a reputation as a torquer rather than a twister, and anyone expecting the easy rpm of a Fiat twin-cam will be disappointed. Yet even though de-smogged to 104 hp – down to 101 hp at 4900 rpm for 1976 – the 2498 cc undersquare six still produced 128 lb ft of torque in its final year. For the rest of the world, not limited by a 7.5:1 compression ratio and equipped with (reportedly troublesome) Lucas fuel injection, the engine made half again as much horsepower, but even that slipped to 124 hp by the end. Had only catalytic converter technology been available earlier.

Weight for the TR6 is quoted from 2400 to 2600 pounds for the later years, and 0-60 mph in more than 12 seconds was adequate, if not outstanding, for a sports car. Funny, but it feels faster than the numbers suggest. The clutch is crisp and the shifter for the four-speed manual (overdrive optional but not on this car) has well-defined if longish throws.

Cranking the steering wheel at slow speeds is a chore and the wheel’s rim is skinny and hard. The wheel is set noticeably high. The rack-and-pinion system gets easier as speed, but bumps in the road keep the driver busy countersteering the effects of suspension travel.

Handling is no doubt worse as a result of raising the TR6 to meet headlight height requirements. Another injustice was the addition of huge, black overriders to the front and rear bumpers in 1973 to meet federal bumper law. Wind buffeting is dreadful compared to modern shapes that direct airflow instead of just standing in the way.

Still, driving with the top down is the only way to go. Lear sprayed this Triumph TR6 a classic British racing green, changing the hideous mustard endemic in the ‘70s (old refrigerators, stoneware, etc.). Sitting back by the rear axle and sighting down that long – if narrow – hood on a summer evening ride through the back-road twisties, heel-and-toeing for the corners, booming off the bends with torque of six cylinders and finding a rhythm in the road is truly a delight in the TR6. You don’t have to be at 10/10ths all the time.

Quality suffered especially toward the end of the TR6’s reign which, due to its length, gave the TR6 the greatest production volume of the TR2 through TR6 models, though it never sold at the rate of its predecessors. Toward the end it had already started become a rolling anachronism, a slightly more modern Morgan, something that Leyland at least subconsciously recognized when it changed the simple outline block letter “TR6” decal (a la Pontiac GTO) on the rear fender to one incorporating the British Union Jack. It’s not nice to play with our emotions like that.

Ironically, the Triumph TR6 makes a better vintage car now than it made a new car when it was, well, new. It’s something that nudges your memory and meets nostalgia’s narrow requirements. It’s an old car, but now it should be.

Addendum: There’s often a debate over what constitutes a sports car. The Truimph TR6 should be Exhibit A. On other hand, the Truimph 2000 roadster is, well, if it is a sports car, it’s not a very good one.