Feature originally published in AutoWeek, July 15, 1985; republished by the author

The two drivers are buckled in and helmeted. Each cranks the giant Chevy motor, mere inches behind his back, and it responds with the vigor and volume of a Midwestern thunderstorm, power that can be felt at 50 paces and sound that vibrates sternums and overwhelms the running monologue of the P.A. The fiberglass body is lowered on each chassis, the drivers give a wave through what would be the windshield if there were glass and then, lining up in the bleach box, the drivers give a quick shot to the throttle. But there’s no smoky burnout that the fans are so used to. The cars just leap forward, front wheels lifting several feet off the ground. But – showmanship aside – it’s enough to clean the Mickey Thompson drag slicks.

One at a time, the drivers line their cars up on the starting line and unleash the full force of their Chevys. Each car comes out in fuel-injected thunder, front end up about 45 degrees, and carries it about 200 feet down the track. Then it’s circle back, wave to the crowd, and line up on the starting line again. The announcer can just be heard over the crackle from the individual exhaust stacks exiting just in front of the big rear tires.

Each driver approaches the starting line, eyes on the Christmas tree. Pre-staged. Staged. Revs come up and everyone is standing as the crescendo of combustion rises. The countdown begins: Yellow, yellow, yellow, yellow, green. Clutch pedals rise and accelerators go down and every eye is on the two cars as a bolt from the start, front wheels high, higher, up until they can rise no further. They’re up against the stops: rubbing blocks of pure titanium at the end of bars extending from the rear of the cars throw a Fourth of July of yellow sparks as they thunder down the track into the haze at the far end, front wheel’s still up as they cross the finish a quarter-mile away.

And the crowd loves it. There’s cheering and clapping and almost no one notices for which lane the win lights are flashing. The P.A. system, now competing with the crowd, calls the times. Nine-five at 160 mph.

Back in the pits, all is not well. The Hemi under Class, the car with the famous name, is OK, but it’s stablemate, the Night Raider, suffered some damage coming down from the wheelie at the far end of the strip. The leading edge of the fiberglass Camaro funny car body hit the pavement – the chassis pivots on the front wheels – lifting the rear wheels off the ground and driving the nose into the asphalt, abrading the fiberglass along the edge and pulling the ‘glass loose from the metal structure underneath.

Toby Ehrmantraut attacks the busted fasteners, drilling new holes and securing the new bolts with large washers to spread the load. New-car bugs. NBC took exception to Toby’s running the car with a Firebird body and the name “Night Raider” on the side, and despite legal wrangling’s still proceeding, Toby’s wheelstander where’s the Camaro skin and a slightly modified name.

No such problem for the Hemi under Glass, though despite its imitation Firebird bodywork and decidedly non-Hemi Chevrolet engine, the name of the original wheel stander belongs wholly to Jack Ehrmantraut. The original H.U.G. wore a Barracuda body and was powered, of course, by Chrysler Hemi. It was a product of the wild first years of funny car competition, before the cars were sanitized for your protection with rules and classes, when all that mattered was who could take his bogus street car-bodied short wheelbase dragster down to the other end of the dragstrip first. It was match racing at its best with meets from one end of the country to the other.

But the wheel standing, explain Jack Ehrmantraut, started by mistake. With the funny cars, they “changed the wheelbase all around, trying to get better traction because back in the mid-‘ 60s, they didn’t have tires like they do now. So Hearst Corp. (which was running its own factory team – everybody had a factory team) said, ‘We’re going to go them one better. We’re going to put the motor in the backseat. Really going to get some bite.’”

They got bite, all right. But with the weight moved back there was nothing to hold the front end down. “It wasn’t worth a damn as a racecar,” says Jack, “but people loved it. They went crazy.”

Hearst wasn’t the only one with the idea of moving the engine back. Within two weeks of the appearance of the Hemi under Glass, so named for its engine under the Barracuda’s expansive fastback rear window, Chrysler brought out its own experiment, the Little Red Wagon, a van-type pickup with a Hemi in the bed. It made a lousy racecar, too. But it didn’t really matter. Those two cars side-by-side down a dragstrip was a show too good to be ignored. Before you could say “Sunday! Sunday! Sunday!” the Screaming Hernia Brothers were on the privacy of your AM radio announcing the appearance of these rolling billboards at a beautiful dragstrip near you.

Twenty years later there are 10 or so wheel standers touring the dragstrips of America. The Ehrmantrauts will cover 100,000 miles this summer as they have, either singly or together, for the past 20 years. Jack was a mechanic for Hearst when the Hemi under Glass debuted, and Toby was literally a babe in arms.

Jack didn’t start driving the car until 1972, but by then Hearst was out of the picture. “They were bought out by Whirlpool, I believe,” Jack recalls, “and they gave up ownership of the car. They didn’t want to own a racecar. So they gave it to Bob Riegel [correct spelling: Riggle], who was the driver at the time and a good friend of mine. I worked then for him. And then he wanted to quit driving, so I started writing it and I ended up buying it from him.”

Since then he and the Hemi under Glass have been to every state except Alaska, they’ve been to Puerto Rico and Australia, Mexico City and all over Canada. Sunday, early in the 1985 season, it’s Cecil County Dragway, a small local track in northeastern Maryland with wood-bench-on-steel bleachers. The week before it had been Phoenix. Monday will find Jack and Toby Ehrmantraut in Baltimore with their oil sponsor before heading home to Butler, Ohio, and the next weekend they would be running in Ohio. But the following weekend it would be Wisconsin and then New Jersey. Then Oklahoma: South Dakota; Alberta, Canada; South Dakota; Alberta Canada; Seattle; Portland. From Portland on Sunday it’s New Jersey on Wednesday night. Each weekend gig pulls about $1,500 to $1,800 per car going up to $2,200 to $2,500 out west. It was the Ehrmantrauts’ only job.

The air is almost-jacket cool and rain is threatening. The first run was pushed up a half-hour ahead of schedule and Lance Keen, the dragstrip manager, was getting edgy, willing to sacrifice the day’s competition schedule to the wheelstanding competition. It’s what the crowd came to see.

“The track has been dormant for so long, we thought we’d put some shows in like this to try to get spectators back. And you can see even on a bad day like today we did pretty good with spectators.” It’s true. The stands, as small as they are, are full.

“We’ve got a lot of shows booked this year,” adds Keen. “Next month we’ve got 16 funny cars, on Mother’s Day.”

The Night Raider and the Hemi under Glass are towed into position again and it’s another perfect run, side-by-side all the way down the track. The crowd goes crazy again, yelling and clapping for the Ehrmantrauts, now almost a half-mile away. The Earth moved for every one of them.

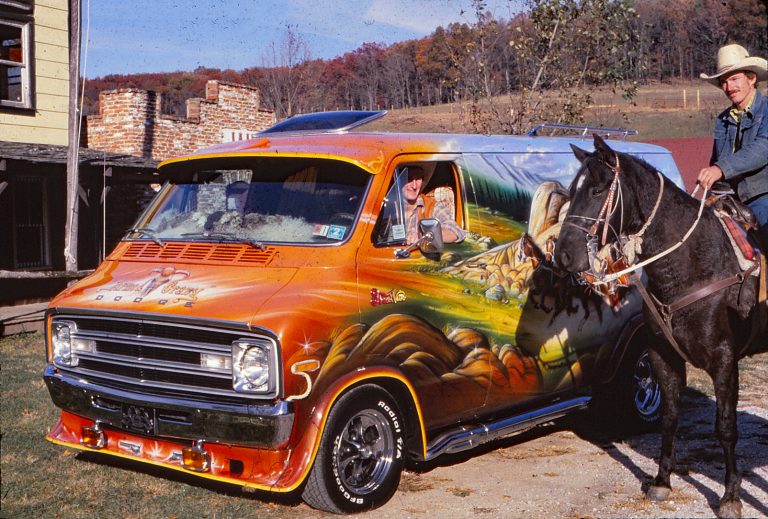

Back in the pits a constant stream of spectators comes for a closer look. In truth, the cars are better looking from the stands. The Hemi under Glass in gold metallic paint, has what looks like a flaming owl airbrushed on the hood, and up close it’s clear that the H” in Hemi is as near as can be allowed without being too much like the famous Hearst “H” logo. And, once a Barracuda, is now a Firebird and the Hemi has given way to the Chevy big block. There’s no fooling this crowd. They know their engines and a good many are old enough to remember the original Hemi under Glass. And some feel a little cheated. The original car is gone, however. “Back then people didn’t care about old racecars,” says Jack, shaking his head. “We just tore them apart and used the parts to build the new car.”

And for the people who come up and say “that’s not a Hemi,” how do you answer?

“That’s right.” Then after pausing for effect, Jack explains, “we quit running (Chrysler Hemis) in 1972. I just tell ‘em when somebody builds one with the Chrysler that will beat that car, I’ll put a Chrysler in it. I think there are only about two Chrysler cars left, and they can’t touch either one of these cars.”

The cars deserve more than superficial examination, however. They are, beneath the carny glitter and plastic, purpose-built racecars. Even Ralph Nader would be proud, sort of: “the car itself is built…to crash,” says Jack. “I have a little note in my shop this says ‘when this thing crashes.’ Not if, when. Because you have to be safe in it. It would be unrealistic to think you are never going to crash one of them. We haven’t in a number of years, thank God, but… And we have been running a lot faster. I don’t know what would happen if we did crash one now. I hope we don’t find out.”

Jack has crashed wheelstanders, though. “First six runs I made I crashed two cars. Totally. The first three runs I made were picture-perfect, just perfect. The fourth run I totally destroyed a car. Rebuilt it and eight weeks later the first run was just great. The second run I totally destroyed it again. I said, “Shit, I don’t think I ought to do this.”

But he kept at it. As result of those crashes, the cars, despite their superficial resemblance to funny cars, are built much sturdier. A funny car will weigh about 1,700 to 1,800 pounds. But the Ehrmantrauts’ wheelstanders weigh between 2,600 2,700. The extra weight is almost completely in the frame. Where a funny car is built from 1¾ -inch 0.09 wall round tube, the main structure of the wheelstanders is a pair of 2 x 4 rectangular channels of 0.12 wall thickness. The cars, replaced every two or three years, are home built. They have to be, claims Jack. “Like a funny car, he goes to a chassis builder and says build me a frame. And they build him a frame. If I go to a chassis shop and say build me a wheelstander, they’d say, ‘Wha’? How?’ We’re experienced. It just works better.”

The engines are set well back and high in the car, the Hemi under Glass with a Lenco two-speed transmission with reverse and Night Raider with an ATI automatic. Short drive shafts pass over the rear axle to transfer cases – built by the Ehrmantrauts – and then back to a “backwards facing” differential. A pair of batteries ride at the very rear of the cars for more favorable weight distribution. The engines are supercharged and run on alcohol and, like their funny car equivalents, have no radiator. At least from a dragracing standpoint, they’re not particularly remarkable. Even oil pickup didn’t have to be moved. On a Chevy engine, the pickup is at the rear of the pan – exactly where the oil goes when the front end is in the air.

Steering during the run is by means of a fiddle brake. Pushing or pulling a lever will apply the brakes on either side of the car.

“Usually it stays pretty straight,” says Toby. “What you usually wind up doing is holding one (brake) on all the way, because of the wind or something.”

The breeze today isn’t too bad according to Toby, it’s coming straight up the track. “But if it’s coming from the side it’ll work you.”

The biggest problem is shifting. Somewhere before halfway down the track they have to change gears. Says Jack, “it’s not (always) the same because, like on that last run I know I went further than I wanted to because the car was going over toward the left, and I was trying to get it back toward the middle of the track because I’ve got to let go of steering brakes to shift the car. And if it it’s headed that way and I let go, it will be off the track before I can get back to it.”

At the far end, the drivers have to ease out the throttle. Acceleration, not the wind, holds a car up, and backing out will ease the car down, at least to the point where the air gets on top of the car. From there it comes down pretty hard.

Toby is kidding his father about needing bifocals to see the shifter, while Jack says no, it’s just, um, middle-age spread that keeps him from bending over far enough to reach it when Lance Keen comes up again. There are reports of rain all around the track and one cloud looks particularly ominous. Could they be ready to run in five minutes?

“I think it’s great. Here’s a guy making money racing.” The realities are the same everywhere, and one former bracket racer knows that very few can make a living driving racecars. Anyone who can do that is something of a hero in his eyes.

A motorcyclist, still dressed in racing leathers, sees it a little differently. “This is neat,” he comments, looking at the car, but turning to Jack Ehrmantraut, “you’ve got to be crazy!” This, mind you, from a guy who just got off a wheelie-bar that turned 140 mph in the quarter mile. The irony is not lost on Jack. “I’m crazy? At least I’ve got a cage around me!”

Someone asked if they’re really racing out there. Sure, replies Jack. That’s how they stay on top, by going faster than anyone else. Besides, do you think the old man is going to let his kid beat him at his own game?

The drivers are suited up again and in their cars. Toby has the Night Raider closed up and running, but there’s a problem with the Hemi under Glass. They haven’t closed the lid and there is far too much activity around the car. Then the announcement comes over the P.A.: The Hemi under Glass will not start. The Night Raider will make the run alone. Toby doesn’t disappoint. It’s another great run, slide-rule straight and calculator perfect, sparking like a Roman candle all the way. Another nine-five, 160-mph run. This may be circus, but these guys ain’t the clowns.

Toby circles around at the far end of the track and, drag chute deployed, he makes a run back down the track toward the start. The fans were getting their money’s worth. He waves as he passed the stands and the cheer can be heard over his engine. The son has learned well from his father. The symbolism is almost too great: The second-generation wheelstander carrying on when his father is not able. But somehow it’s right and just how it should be. One wishes the best for these American nomads. Ringling Brothers has nothing on them.

Addendum: In 1991, the Ehrmantrauts were still at it, though Jack’s wheelstander was now an ersatz fifth-generation 1986 Dodge Charger, essentially the coupe version of the Dodge Omni, and Toby was driving the wheelstanding version of a 1957 Chevy convertible. Father and son were caught on video at the 1991 Can-am Nationals London Motorsports Park.

There was a recreation of the original Hemi under Glass more or less recently, and in 2016, Bob Riggle rolled it, and with Jay Leno in the passenger seat. It would make a rather dramatic segment for Leno’s garage. Here’s a report on it, appropriately enough, in AutoWeek.

More information about the original Hemi under Glass, Street Muscle Magazine has a great article.

Check out my review and drive of the 1971 Plymouth Barracuda Hemi’ Cuda.