History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek December 24, 2001

Harold Metzger gently chided me for having chirp the tires of his 29 – Cabriolet. “Well, we certainly know it has enough power to burn rubber!”

I had halted on a hill having failed to negotiate a downshift on the non-synchronized gearbox. (One doesn’t get much practice double clutching while driving modern automobiles, does one?) Rolling backward, I had made the tires bark after reverting to low gear for the climb. Almost back to Metzger’s Swiftwater, Pennsylvania, home, I left it in first for the remainder of the drive.

Not that Metzger was worried. The Nash’s drivetrain was easily up to the abuse. Learning to drive was much more challenging 70-plus years ago. Nonsynchro transmissions require talent, and the starting ritual of retarding the spark, opening the hand throttle, setting the choke, turning the ignition key and then stepping on the starting pedal had to be learned. Not to mention setting the lever that diverted exhaust heat to the updraft carburetor, depending on whether the weather and the engine were warm or not.

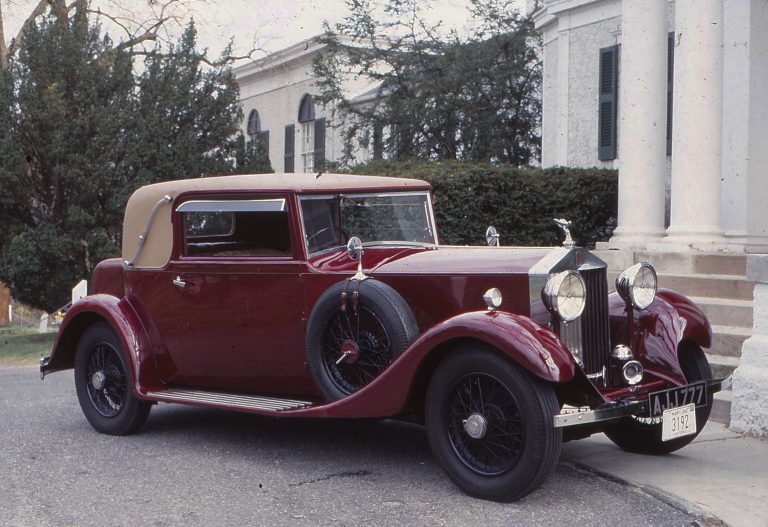

The Nash was an upscale automobile, on par with, say, a Buick. This Cabrio was in the Nash 400 Series, a model 461 to be exact, with two seats under a folding fabric top, plus seating for two in the rumble seat. With the top raised, the hand-cracked glass side windows made a snug seal, and the heat off the engine kept the interior temperature on all but the coldest of days, when one might wish for an aftermarket heater.

The engine had been new in 1928, with a special feature that allowed Nash to bill it as “The Car with the Twin-Ignition Motor.” The overhead-valve six had two spark plugs per cylinder: one to one side of the head, which formed a flat top to the cylinder; the other plug projected opposite into the cylinder itself, the piston not reaching the top of the cylinder as per usual. Nash boasted that this “twin-ignition, high-compression, valve-in-head motor “– though having a 5.0:1 compression ratio – didn’t require expensive premium fuel. So much for cynics who don’t think Detroit – or Kenosha, Wisconsin, in this case – wasn’t looking for more efficient engines even in the ‘20s.

The engine has several remarkable features, including an impressive 12-lead-wire distributor operating off two coils. The wires for the spark plugs in the cylinder walls actually go through six screw-in tubes through the block’s water jacket! The engine also had a three-and-3-sixteenth-inch bore and a five-inch stroke, so while the engine was officially rated at 28 hp, the connecting rods had a lot of leverage on that long-throw crank. The torque was noticeable while driving; the Nash was able to saunter up most hills in high gear.

The interior featured “wood graining,” paint on metal panels simulating fancy wood trim, while real wood still helped comprise the Nash’s structure. The centrally mounted brass-with-gold-trim instrument panel had an ammeter, engine temperature gauge, drum-type speedometer, a fancy electric clock, a U-tube fuel gauge and an oil pressure gauge (the engine had full pressure lubrication). Four-wheel drum brakes, internal-expanding front and external-contracting rear, were cable-operated but mechanically balanced site-to-side and front-to-rear. Bijur automatic chassis lubrication, hydraulic lever-action shocks and wood artillery wheels made the Nash, as advertised, “a new and finer motorcar.” That’s an assessment hard to dispute as Metzger’s Cabriolet quietly glided smoothly over winding, bumpy roads.

The car had sat idle until 1983, when acquired by Metzger, who finished – mostly – restoring the car last spring. It had been bought for $50 in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1949, by a Mt. Pocono, Pennsylvania, college student who overheated it on the way home from school in 1950. The overheating cracked the head, a form of abuse the Nash couldn’t stand.

He should have stuck with burning rubber.