History originally published in AutoWeek April 11, 1983

Find the roughest road you know: 40-year-old concrete, cracked, broken and rudely patched. Knife-edge ridges and holes. A road that rattles and shakes the torque out of every nut and bolt of a normal car. Loctite and all.

Drive the BMW 2000 Tilux there first. The ride will astound you, supple and smooth, and you will drive down that road faster than you have ever before. The BMW soaks it all up and ask for more. You might be tempted to believe that it’s all cushy shocks and springs, but there’s more.

Change the venue. A winding road, bituminous velvet unrolling like a memory over and around rounded hills and farms with white painted fences, thoroughbreds and horses to be rode to the hounds. Work the Bimmer through the gears, twisting it to redline, letting it whine like a lafhs spinning out horsepower turned from the solid billet. Brake for a corner and discover that you been traveling at almost double the posted limit. In complete safety.

The corners have lean then you remember in a BMW, but push it harder and discover a bond, a grip underfoot that can be trusted. You can build a rhythm with this car, work it without feeling guilty. The car enjoys it, asks for it and comes back asking for more. You could do this all day, every day, for the rest of your life.

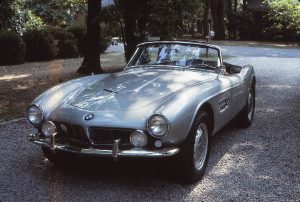

It doesn’t seem fair that such a simple looking, plain looking car should be so good. BMW, after the very traditional 502, the elegant 507, the plebeian Isetta and puckish 700, which altogether almost consigned the Munich firm to the oblivion of subsidiaryship to Mercedes, stuck to the middle ground when it introduced the 1500 in 1961. The new model was so bare that a customer wanting a radio had to cut the metal dash himself, but under the rounded three-box body was a technological revolution: Fully independent suspension and an overhead cam engine. While not “firsts,” they were, to say the least, unusual on a moderately priced automobile. Front disc brakes were frosting on the cake.

Production on the 1500 was not able to begin until 1962, but the German public knew value when it saw it. The factory had a hard time keeping up with a backlog of orders when the lines finally began to roll.

The 1500, though, was only the first of BMWs “New Class.” Model proliferation followed as Munich reached to capitalize on the new-found popularity of the marque. By 1966, the 1500 platform had sired the 1800, the 1800 TI, 1800 TI/SA, 2000 C, 2000 CS, 1600-2, 2000, 2000 TI.

And in 1966, BMW brought out the 2000 TI-Lux. The “2000,” of course, indicated engine size, the original displacement having been bored and stroked to an actual 1990cc. The “TI” stood for “touring international,” which meant as it had with the 1600 TI that the engine was equipped with two twin-throat side draft Solex 40 PHH carburetors. The “Lux,” naturally enough, was for luxury.

The 2000 had premiered rectangular, almost trapezoidal, headlights for the sedan series, and also had revised rear lights, but the TI was offered with round headlamps and the old-style rear lamps, thus allowing the twin-carb engine to be offered in a bargain price. Adding the “lux” brought back the wide-band headlights – in Europe only, of course. US versions were fitted with quad sealed beams. The Lux models were also treated to upgraded interiors. Vinyl covered more of the inside metal, and the dash was trimmed with real wood which also extended back along the doors. One no longer had to perforate the dash to mount a radio. A consolette below the dash held the Blaupunkt.

From its introduction, the Tilux (as it became known in 1968) was the class of the New Class sedans. Only the coupe-bodied 2000 C/CS was more expensive. Although it had a tauter suspension and handled better than the Tilux, it was about a second slower through the quarter-mile: The Tilux, weighing in at just under 2600 pounds, was almost 100 pounds lighter than the coupe, scooting through the quarter in the low 17s. The superior aerodynamics of the coupe better the top end on the Tilux—110 MPH—by five, which on the autobahn was more important anyway.

The engines of the two cars were identical, however, and immediately recognizable to even the most recent Bimmer fan as a variation on a familiar theme. The 1990cc SOHC four, under a wide aluminum valve cover is canted at 30 degrees from vertical. With a 9.3:1 compression ratio and an oversquare bore and stroke, power was rated at 135 [BHP] at 5800 RPM, 400 RPM below redline. This compares with 114 BHP from the base 2000 engine with its single throat downdraft carb and 8.5:1 compression ratio.

Fittingly, the cab is equipped for the tech as well as the Lux, from seats that provide lateral support unobtrusively, to full instrumentation consisting of a 120-MPH speedometer on the left, a smallish tachometer in the center, and a speedo-matching clock on the right ringed by no less than seven gauges and warning lights: Gauges marked “Tank” and “Temp,” and lights labeled “Tank,” “Blinker,” “Oel,” “Ladung,” and “Fernlicht.” So much for international marking.

The BMW 2000 Tilux was a driver’s car, albeit one for someone who needed the extra room of a sedan with a comparable ride and a door for everybody, and the real test of a driver’s car is in the driving. That is where the Tilux excels, from turning corners into curves to shortening the straights with surprising speed, to flat out consuming the road, any road, with offhand aplomb. Just think of it as a sports car for someone with friends.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.