Feature originally published in AutoWeek November 24, 1986

The Dino, finally, has arrived.

Criticized at the time of its introduction for being too slow, too small and having too few cylinders, it wasn’t considered a true Ferrari. Real Ferraris have 12 cylinders, the purists said. Real Ferraris didn’t have engine castings and wheels with the Fiat name on them.

Recently, however, the Dino has been gaining appreciation from purists and the resale market as well. Where once the Dino, in poor condition, could be had for less than a new Pinto, a clean Dino will now fetch over $30,000. Reliable rumors place the recent sale of 246 GTS at over $40 grand. That’s probably a record, but in any case it’s proof that the Dino – the 206 GT, 246 GT, and 246 GTS – has been vindicated.

The Dino name began in 1956, the first of three different V-6 engine series. Enzo Ferrari, in his memoirs, credited his son Dino with the concept of the engine, describing himself and Vittorio Jano at Dino’s bedside, with Dino expounding on the logic of the layout. How much Dino actually influenced the design is subject to conjecture. The experienced Jano may have been sympathetic to the ailing 24-year-old, but certainly he had ideas of his own. In the end, the younger Ferrari died never having heard the V-6 run. The father named the new engine in honor of his son.

The original Dino was a 65-degree dohc V-6 ranging from 1.5 to about 3.0 liters and was used in Grand Prix and sports car racing. The second series so-named was introduced in 1957, 60 degrees sohc V-6 used primarily in customer sports cars.

Like the first series, the third Dino V-6 series was a 65 degrees dohc engine and was created to meet the stock-block requirements for Formula Two. Designed by Franco Rocchi of Ferrari, it was destined for the Fiat Dino Coupes and Spyders which debuted at the Turin Auto Show in November 1966. At the same show was the Dino Berlinetta GT, a working prototype that was actually a precursor of the Dino 206 GT which was to appear at the same show year later.

There is no doubt that the Fiat Dino and the 206 GT were production vehicles, if only on a limited scale. Before the chicken and egg question of raising versus production roots of the engine one need look only to the April 1965 appearance of the Dino 166P. This sports prototype racer, a single example, was campaigned all through 1965. Another Dino-powered racer followed. Of course, one could say racing was just Ferrari’s way of testing the engines. And at that, one might not be too very wrong.

Production of the 206 GT began in late 1968. Scaglietti built the aluminum Pininfarina-designed bodies and Fiat the aluminum-block engines. The chassis was a traditional ladder frame of welded oval and rectangular steel tubes and the suspension a very racer-like unequal A-arms with coil springs and anti-roll bar front and rear. Brakes were four-wheel disc.

The V-6 rested transversely amidships with the five-speed transaxle. The engine was all-aluminum, made in Turin by Fiat (the castings all have “FIAT” on them) and installed at the Maranello factory. Bore and stroke were over square that 86 x 57 mm for a total displacement of 1987 cc. With three Weber 40 DCF downdraft carburetors, power was rated at 180 bhp at 8000 rpm, good enough for 0-60 in 7.5 seconds, the quarter-mile in 15.5, and a top speed of 140 mph. With the “Dino GT” script on the rear and a yellow Dino badge on the nose, the only thing the 1984 pound bolide lacked was the Ferrari name or the prancing horse emblem.

The 206 GT had a limited production run. Ferrarologists debate the exact number, but the factory says 150 were made. It has been suggested, though, that, based on serial numbers and so forth, as many as 500 may have been built.

The 206 GT was succeeded by the 246 GT at the Turin show in 1969. Outwardly there was little difference between the two. The body shape was the same, though the roofline was raised 3 inches (to 45 inches) and the wheelbase stretched from 90 inches to 90.3.

Differences which could not be seen were more significant. The aluminum body of the 206, became steel on the 246 and the engine block went from aluminum to cast-iron. Weight went up almost 400 lbs, to 2380. Horsepower, and the European version (it was not yet sold in the US), went to 195 bhp, netting minimal gains in acceleration, dropping the quarter-mile times to about 15.1 and 0-62 the low sevens. Top speed edged up to about 145 mph.

The appearance of the 246 GT is usually attributed to Maranello’s feeling a need to enlarge the engine to match the performance of other high-performance GT cars, specifically the 2.2 liter Porsche 911 S. However in June 1969, the Fiat took 50 percent of Ferrari SpA’s stock and effectively took over its road car production. This arrangement probably suited Enzo Ferrari eminently, as production automobiles had always been only a means of supporting the racing effort. With the bottom line guiding the production side, more producible cars with steel bodies and iron blocks made more sense.

An open air Dino, 246 GTS, followed with a lift-off roof session yielding a targa-type roofline. It was the most civilized Dino yet, available even with air conditioning. Emission controls on US bound 246 GTs and GTSes dropped the power to 175 BHP. Thus the Dino changed from spare and uncompromising to something that was, if not exactly practical, at least a little more oriented to the needs of its passengers.

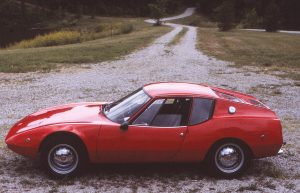

We assembled three Dino’s for this article: a red 206 GT belonging to Otto Meletzke of Annandale, Virginia; the white 246 GT of Alan Rash of Bowie, Md.; and the red 246 GTS of Nick Ward of Rockville, Maryland.

Side-by-side the dissimilarities of the cars were obvious. The 206 does look lower and the extra length of the 246 can be seen between the door and the rear wheel arch. Ward’s Spider shows the full effect of federalization, with DOT side lamps and recessed front turn signals.

Each of the cars is distinctive. Meletzke’s 206 has a low serial number, 00110. Nobody but nobody reads serial numbers like a Ferraristi, but it is significant in this case because it suggests Meletzke’s 206 is one of three pre-production Dino’s (not to be confused with the prototypes) assembled by Pininfarina. Also, it’ engine block is marked “Dino S” (production blocks were marked “FIAT”).

The 246 GT of Alan Rash was the New York Auto Show car, and is perhaps the only Dino that came with the Ferrari name on it (though many owners added it). Nick Ward’s 246 GTS is simply one of the best original 246’ is around.

Driving the three Dinos revealed not so much differences as similarities. All three are difficult to get in, the coupes because of their low roofline and the spider just because of its lowness and limited room under the steering wheel.

The engines – and we’re speaking in the collective – fire up with a nasty growl and a nervousness that befits a small high-performance engine. It’s fun just to burble around and flirt with the Yuppettes, but that’s nothing compared to nailing the throttle. At 4000 rpm begins the sound of a sharp steel radial saw biting into a well-cured two-by-four.

The shifter has been criticized, yet I experienced no problems guiding the gated lever from slot to slot, at least not from the linkage. The pattern of the five-speed, however, is the “racing” layout, with first outside of the H, back and to the left. But the reach isn’t awkward and it’s just a matter of remembering where to move the stick.

Handling is, of course, the cars forte, what with the midship engine and the race car suspension. The rack and pinion steering is light, accurate and cat quick and the limits of cornering are well beyond what I was willing to explore on a public road. Delightfully, it also has a good ride – one of the things more appreciated in recent years.

So we have a car that had acceleration that, if not the absolute, was nothing to be ashamed of, stellar handling, and looks that, if not everyone’s cup of espresso, was, Meletzke’s 206 recently won a Ferrari meet’s Ladies’ Choice trophy and what more do you need than that?

Yet the Dino’s reputation suffered. Some of it, of course, was earned. A problem with second-gear shifters was there year after year, and Dinos came equipped with two ignition systems: Dinoplac electronic along with regular coil and a switch to select between them. It could have been thoughtful redundancy, except that the Dinoplac was non-functional more often than not. The air conditioning and Dinos did little more than keep itself cool. And Dino’s rusted as badly as any other Italian exotic.

The criticism that the Dino was NARF – Not A Real Ferrari – because it didn’t have 12 cylinders or because it didn’t have the Ferrari name, was the unkindness cut of all. It is true that Dino was to be a marque separate and junior to Ferrari. But Enzo so named it as a tribute to his son. The Dino was as much a Ferrari as the Old Man himself.

But that doesn’t explain the revival of the reputation of the Dino road cars. The answer perhaps is found in the events that followed the demise of the Dino 246 GT/246 GTS after 1974: The 246 was succeeded by a different kind of car, the Dino 308 GT4. The Bertone-styled 2-plus-2 was powered by a transverse midship V-8 and was subject to the same NARF criticism as the 246 GT. To such an extent that Maranello issued a technical bulletin authorizing the use of “Ferrari” identifications on the car.

The GTB4 was replaced by the Pininfarina-designed Ferrari 308 GTB/GTS (and assorted variations), mechanically a direct descendent of the 308GT4. Although it too met with NARF – not only was it a V-8 but it had at first a fiberglass body – it has endured and become the largest selling Ferrari of all time. Exit, except for a few diehards, the 12-cylinder requirement for Ferrariness.

Another factor has been the changing status of the Dino. No one uses a Dino for everyday transportation anymore. Dino’s are pampered and cared for, and it really doesn’t matter if the GTS’s roof leaks – it doesn’t go out in the rain. As a “toy”, the dDino’s reliability problems are minimal, and, as the price rises, the more likely it is that the purchaser is able to afford the maintenance the Dino requires.

The vindication of the Dino is most easily measured in dollars and cents, but money is a crude measure of desire; Dino lust is rising like the howl of a 65-degree V-6 at full throttle. The kid is here, the father’s tribute to the son is hot.

The Dino is back.

Go back and read the third paragraph again: “Where once the Dino, in poor condition, could be had for less than a new Pinto, a clean Dino will now fetch over $30,000. Reliable rumors place the recent sale of 246 GTS at over $40 grand. That’s probably a record…”

Now place a mental thumb on that paragraph while visit classic.com and look at recent sale prices—not asking prices, but sales—and the record high for the past five years is (hold your breath) $853,000. The most recent, at the time of this publication, was $438,000, and that was below the current “moving average.”

You don’t need a present value calculation to know that far exceeds inflation. If you’re just in it for the money, that’s a better investment than baseball cards. And you can’t pick up girls with baseball cards.

The Dino is more than back.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.