History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek October 15, 1984

At 90 mph on the sparsely traveled two-lane highway, the big Mercedes is at ease, loping along, as comfortable as a Divine Right king in an election year and twice is safe. I am securely fastened in the passenger seat by the wide lap belt, and secure in the knowledge that the greatest hazard possible is at the radar detector might malfunction. But the road is wide and rolling, the shoulders generous and open, and the 300SL Coupe is piloted by its owner, Larry Pfitzenmaier. Pfitzenmaier is a Navy pilot, and I could be in no safer hands. I am reduced to observing gnats sacrificing their demand to lives against the SL’s windshield while scouting for a photo location and discussing the relative merits of the various versions of the 300SL.

Pfitzenmaier’s SL is No. 6500300, the 300th manufactured in 1956 and 88 from the last of 1,400 production coupes. At 90, conversation is easy, with only a subdued moan from the engine and a faint rustling around the vent windows. Pfitzenmaier recalls that he was just out of Navy flight school when he bought the car, December 14, 1968. All of his classmates were buying fast cars, mostly of the Detroit supercar genre, and he bought the Mercedes, a car with funny doors, to have something different.

But how things have changed in the years intervening. Now he’s on the Board of Directors of Gullwing International, a group of some 900 members worldwide, dedicated to the preservation and enjoyment of the marque. He has become a believer. Not that the car hasn’t earned it. During the first years of his ownership of the car, he used it daily as transportation. He took his honeymoon in it. Use gradually devolved into pleasure and trips to the shows, but over the years the car has displayed the brick-like reliability for which 300SL’s are famous. All major restoration – paint and interior – was completed by 1971, and the car has required no major service since then.

It’s more than reliability, though. Pfitzenmaier points out that upon its introduction in 1954, the car was head and shoulders above its contemporaries, listing off an honor roll of the era: Austin Healey 100, Jaguar XK-140, MG-TF, Porsche 356A, six-cylinder Corvette… All nice cars, to one degree or another, but not in the class of the 300SL. (Hold your letters. That’s his opinion.)

He does have a point, however, when he calls the SL “the most technically advanced production car of its era.” The model began as a race car, debuting in the 1952 Mille Miglia less detailed and refined than the final production version. It didn’t win, as legend usually requires, but it did finish second. Notice was served. The Mercedes sports car was to take the top places at Berne, Switzerland, the Nurbergring, Le Mans, and the Carrera Panamerica in Mexico. Then, having proven its point, next Mercedes withdrew from sports car racing.

But the 300SL not only made a point, it also made a reputation, one in which U.S. importer Max Hoffman (notice how he always got involved in these things) saw a potential to exploit. Ergo the production 300SL, a car built in Europe with U.S. sales in mind. It made its first appearance at the New York Automobile Show in February 1954, with the really big production numbers (if you can call 867 big) coming in 1955.

As a race car turned road car, the model stayed remarkably true to its origins. Like the racer, the chassis was a complex spaceframe of chrome moly tubing. It was, in fact, this space frame that required the car’s unusual doors, as it extended well up into the side of the vehicle. Also like the racer was the fully independent suspension, with unequal-length A-arms up front and swing arms in the rear. And also like the racer was the six-cylinder engine, but – this must be unique – it actually made more power in the road version than in the racer.

The M198 engine used in the production SLs produced 220bhp at 5800 RPM from three liters. The racer’s 195bhp engine was carbureted, but for tractability as well as performance, Bosch fuel injection was installed. The injection nozzles screwed into the cast-iron block and sprayed directly into the combustion chamber which, because the top of the block was faced off at 20 degrees, was shaped like a scooped-out section of the block as well as the piston and the head itself.

The head was cast in aluminum and carried a chain-driven single overhead cam which opened the valves through rocker arms. The vaguely erotic intake manifolding with its 14-inch ram pipes dominates the under head view, but is possible only because the engine is canted to the left. Coming out on the same side that the intake goes in, the exhaust travels through stainless steel headers to a two-and-five-eighths-inch exhaust system. An oil tank for this 16-quart dry sump system is in the left front fender.

A four-speed transmission was fitted, and the choice of four axle ratios from 4.11 to 3.25 was available. But, rather than provide different drive gears, different speedometers came with the various ratios, the 3.25 gear getting a 180-mph unit instead of the 160-mph speedo’s that came with the others.

In what must be the ultimate in drum brakes, the 300SL has 10¼-inch-diameter Alfin drums with 3½-inch-wide shoes, more than enough to slow us down for a side road that looked promising as a photo site.

We completed the photo session with the sun just having slid beneath the horizon but with sufficient afterglow left me to drive the car in daylight. Believe me, it’s hard enough to get in on the passenger side as the “sill” is quite wide and difficult to step over – it must have been very entertaining when the miniskirt was popular – but the driver’s side, with the steering wheel in the way, is ridiculous. Mercedes even fitted a special release that allowed the steering wheel to pivot down, but all that does is move it in the way from one’s legs to in the way of one’s abdomen.

The SL is strictly a two-seater, and despite the cars width, driver and passenger sit fairly close together. Behind the seats is specially fitted luggage, strapped into place, thoughtfully provided by the factory which had used up virtually all of the trunk for the spare and the 34.5-gallon fuel tank underneath it.

The engine starts with an easy roar of anticipation, but underway in first gear the initial impression is one of heaviness. The steering is truck like, and a heavy-duty whine comes from the gearbox. But it disappears with speed, replaced with steadiness at the wheel and a hammering metallic crescendo that would be the pride of a Caribbean steel drummer. In a steady speed the sound diminishes, but backing off produces a lovely, although totally different, sound. One could speed up and slow down all day long just to listen.

Indeed, it is capable of remarkable acceleration. The increase of power is quite noticeable as the revs rise, most likely the ram pipes coming into play. Pfitzenmaier has recorded better fuel mileage at sustained average speeds nearing 100 mph (out West, in the good old days before 55) than at lower speeds.

Ventilation is very good, and at speed there is no regret that the side windows do not open. (The cabin exhaust vents, over the rear window, are not baffled, however, so be careful at the car wash.) At slow speeds the car can get quite warm in the summer, but it is possible to drive slowly with the gullwing doors open, even if it does attract a lot of attention.

In fact, one gets the idea that Pfitzenmaier, who bought the car largely because of those portals, would rather that the car had more ordinary doors so that the less arresting characteristics of the car, aesthetic and technical, would be appreciated more. After all, the 300SL would have been a great car regardless of its doors, for when the factory took it racing in 1955 it won production category in the Mille Miglia, the production GT event of the GP of Sweden, the Stella Alpina rally, the Coppa Dolomite rally, the Liege-Rome-Liege rally…

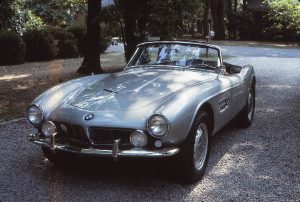

Max Hoffman was a New York-based importer who dealt in European makes large and small. As such had influence with dealers–in the early ’50s when the VW Beetle was not yet a household name, Hoffan required dealers to take two of the slow-moving German economy cars for every Jaguar he’d deliver. Hoffman also talked BMW into producing the stunningly beautiful BMW 507...and the road version of the racing 300SL.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.