History originally published in AutoWeek July 30, 1984

Highway 51 rides the backbone of America. The southern end is anchored at New Orleans, the other in northern Wisconsin. In between, the asphalt runs through Centralia, Illinois, which, at least Before California, was about as close to the US center as a city could be. Some 30 miles south on US 51 is Du Quoin.

Now Du Quoin, what with its French name, would hardly seem to serve as the epicenter of American racing, but on Sept. 5, 1960, it might as well be the the center of the universe to one Anthony Joseph Foyt. Foyt made that day a watershed of racing history by taking his first USAC checkered flag in a Champ car race on that oval mile of Illinois soil.

In those days, when the USAC championship was something done on dirt as well as on pavement – even more so, in fact – and if the new “lay-down Offys,” with their offset driveshafts and lower profiles were ideal for the paved tracks, they were wholly unsuited for the dirt half of the schedule. For that one needed a “dirt car,” and those made by Wally Meskowski were the best. It was a Meskowski car that Foyt was driving that memorable September day.

And mechanics. One didn’t win races without a skilled set of hands at the wrenches, and – no slight to Foyt’s own mechanical talents – one of the best mechanics on the USAC trail was George Bignotti. And Bignotti was Foyt’s mechanic in 1960. What a team: AJ Foyt in a Meskowski Dirt Champ Car wrenched by George Bignotti.

Make it even better: This team would be wearing the label of the Bowes Seal Fast Special, a name that went back to the infancy of American racing. It would be on his lay-down Indy car as well.

Foyt won the USAC championship in 1960, with wins at Du Quoin, the Hoosier hundred at the Indianapolis Fairgrounds, Sacramento, and the Phoenix finale. Every one is a dirt track, and every win in the dirt car.

Dirt track cars – Champ cars, sprinters, and midgets alike – are amazing devices. On one hand, they must be lightweight, fast and agile. It’s a prerequisite for winning races. On the other, however, they must be anvil tough to survive the humps, holes and ruts of the dirt track.

Nevertheless, dirt track cars have long careers. The car that AJ had won with in 1960 was still running in the mid-70s, with the list of drivers including Bobby Marshman, Lloyd Ruby, Gary Bettenhausen, Rolly Beale and Daryl Harrison having sat in the same seat as AJ. None of them, though, managed to win in the car. When it came up for sale one last time, it was bought by a pair of dirt track enthusiasts, Lynn Paxton and Bob Benchoff. Paxton was driving for Benchoff at the time, and when the pair decided to give Champ dirt cars a try, well, what could be better than the old Foyt/Bignotti/Meskowski car? Old, yes, but a restoration natural after they were through racing.

Well, Paxton didn’t win with the car either, that honor being reserved solely for Foyt, but AJ iced the investment of the deal by winning Indy the fourth time. Paxton and Benchoff went partners on restoration at the end of the season.

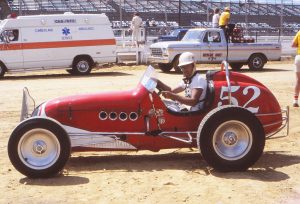

And a finely executed restoration it is. Paxton decided to restore it to the Langhorne ‘61 conditions, and then carefully researched it to know where he can vouch for the location of every bit of metal, rubber and paint, except the kill switch, which was there somewhere, but no one remembers exactly where and the pictures don’t show. Why Langhorne ’61? Well, Foyt won there, and won with his big number one on the car.

The car is resplendent in its red and black on white livery, and, without the little dings and chipped paint that a racer inevitably picks up, probably prettier than it ever looked on the Champ trail. Otherwise it is just as it was then, from its chromium snout to its 55 gallon rump.

There’s something disturbingly familiar about the car, like bubblegum cards, cicadas in the summer, or girls in shorts just a little too tight. And really, that’s as it should be. The basic formula for the USAC Champ dirt car has remained constant for decades, and anyone who has pushed a toy car across the floor has at one time or another handled a miniature dirt car. Changes have been evolutionary.

This car is a perfect example. It was the latest rage, a “four bar car,” meaning that the solid front and rear axles were suspended by two torsion bars apiece, the front torsion bars being the latest twist. Before that it’d been coils. That constituted a big change in this corner of the sport.

Otherwise it was typical. Power is 255 Offy, an all-American engine with dual overhead cams, Joe Hunt magneto, Hallibrand fuel injection on the left side, the world’s simplest headers on the right. There is no onboard starter, the car needing either a push or an external starter with a 40-inch drive that slides in under the grill.

The body is all aluminum over a chrome-moly truss-type tube frame, with a 1½-inch-ish main tube triangulated with smaller tubes of the same material. It’s in the rules. The egg-shaped lump is the oil tank: The Offy requires a 16–18 quart oil supply.

Monroe shocks are used, two at each corner except the left rear, where there is only one. The suspension is liberally chromed and has more zerk fittings than you can shake a whole forest of sticks at. This car has only a lower radius rod; the more common two radius rods per side was not used because the four rod system had a tendency to bind. The car also has Hallibrand spot brakes at each wheel, with provisions for an extra pair on the rear axle for the few paved tracks on which the dirt car was run. These were operated by hand.

The Offy engine is mated to an Offy gearbox that’s in full view of the driver, and power goes to the rear axle via a similarly visible torque tube. The cockpit is not a friendly place for a lady, and it threatens the best of men. It starts with getting in, there is a matter of sitting astride the torque tube, and the angled-back shift lever threatens one’s groin.

Instrumentation is minimal, with the big tach, and temp and oil pressure gauges. There are two pedals, with the clutch on the left and a huge throttle pedal on the right. There’s no brake pedal because that’s done by hand. On the right side of the car, looking like a handbrake, is a weight jacking lever. It’s used to compensate for decreasing fuel load (55 gallons is significant in the 1,425-pound dry weight class). Under the dash is a Dial-a-Check, a fuel-line valve for affecting fuel mixture richness from the cockpit.

Yet, for all its racer starkness, it’s a comfortable place to sit. The wraparound seat holds the driver more securely than a horsehide sphere in a Rawlings first baseman’s mitt. In addition, drivers used a “harness,” a strap from the left side of the car looped around the right shoulder to help fight the G-forces on those long left turns on laps that average 100 mph.

Strapped into this car, AJ Foyt won the championship not only in 1960, but also in ‘61 and ‘63. He probably would have won in ‘62 as well, were it not for a temporary ego-caused clash between Foyt and Bignotti. Foyt won his last race in this car before leaving, won none while away, and won his first race back in it (although as the Sheraton-Thompson special).

The Foyt/Bignotti/Meskowski car is a survivor. Surprisingly, despite the number of drivers and the even larger number of races, it came through relatively unscathed, unusual in the rough-and-tumble world of the dirt tracks. Now retired from active duty, it makes most of its appearances at events put on by the Williams Grove Oldtimers, a Pennsylvania-based group dedicated to the preservation of dirt track history. Most of the mile tracks, however, are gone, variously subject to finances, urbanization, changing times…

But Du Quoin remains, a living tribute to the Champ dirt cars and men who drove them. Or is it, perhaps, the other way around?

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.