History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek June 9, 1986

Bound in this white plastic projectile I dance on the offset pedals and coax the stubborn column shifter from gear to gear, surrounded by the peculiar note of the two-stroke triple. I brake early for the corners and then slither through the corners at full throttle, the skinny radials scratching for purchase on the asphalt. Up ahead is a similar shape but in silver and emitting the raspy buzz of a lightly muffled four-stroke engine. It, too, attacks the corners like a ferret chasing supper. We’re not racing, not hardly, but neither is about to yield upper hand.

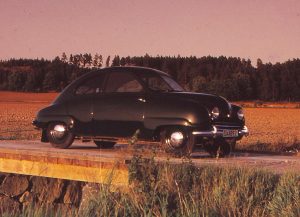

Ahead is Alan Tetervin, owner of the ‘68 Saab Sonett II he’s piloting. I’m in the ‘67 Sonett II of Florida sculptor Jacques Dellavale. We planned to motor out to a photo location from Allen’s Scandinavian Import Service, shoot some pictures, and then swap cars for the return to Allen’s shop in Rockville, Maryland. And that’s what we did, except that the verb “motor” seems to sedate for craziness describable only by the juvenile phrase “Boy, that was neat.” Maybe crude and surely unconventional, Saab’s ‘60s sports car is a lot of fun to play with.

Let’s start at the beginning, and that’s walking around the cars. Despite being the product of a Swedish aircraft firm, they look like kit cars, with exposed grommets holding the body to the frame and add-on scoops on an over-trendy Coke-bottle, fastback shape.

It’s an impression not changed by getting in through the smallish doors, difficult only when not compared to loading luggage. The Saab will carry lots of gear, but only in pieces small enough to fit between seats and rollbar or through what is surely the world’s smallest tailgate. The seats are hard and thinly padded, but well bolstered and slightly raked. Gauges are in a home-built looking dash of mahogany-covered plywood.

With the two-stroke the choke must be used even when the engine is warm, but the engine will stall if it is not pushed in immediately, even when the engine is cold. The engine settles into a popping idle and with moderate throttle and a lot of clutch the Sonett can be coaxed into movement but don’t expect much unless the revs have been brought up. The powerband, beginning at 4000rpm and running to the 6000rpm redline, is narrow as a tight rope and one had best not fall off as there is no net. Down on the rev range, the two-stroke falls flat. But rev it to start up and you’re likely to chirp the tires.

Freewheeling, a vestige of pre-injection two-stroke tech, can be locked in or out. The latter is better. Freewheeling feels like severe turbo lag. Lock it out and response is immediate. Just plain dumb is a column shifter for the four-speed. It hangs up between gears and is an ergonomic nightmare. Acceleration was adequate for the era (0 to 60 mph in about 12.5 second), but selecting forth is like running into a marshmallow. Top speed may be 90 mph if one has patience, though 80 is a more practical limit.

It sticks surprisingly well through the corners and, despite the engine-out-front FWD design, understeer is manageable. Lift the throttle to tighten the line, hit it to run wide again, although freewheeling ruins this effect.

Allen’s V4 Sonett also has freewheeling but naturally it was locked out for the return trip. Saab replaced the two-stroke with the V4 ostensibly to attract American scared off by the peculiar triple. More likely Saab saw little chance of the two-stroke surviving the coming emissions laws. The V4, a cast-off Ford’s aborted Cardinal, had been tested by Ford in Saabs. The combination was obvious. Though it fit easily in Saab’s sedan, the carburetor on the V4 would have projected through the Sonetts hood, a problem solved by the ugly power bulge.

Except that there wasn’t much more power in the 1500cc V4 than the twos-stroke and V4 was 70 pounds heavier, all hung out over the front end. Which should have, and did, make the V4 Sonett a less competent sports car. The two-stroke, however, was tuned about as far as it could go. The V4 had much more capacity left in it, and Alan has used much of it, making his V4 into “what Saab should have made it.” The breathing has been improved with giant Saab Group 2 valves, big ports, a semi-radical cam and a modified Weber 2bbl downdraft carb. Konis and cut coil springs lower the car and improve the handling, if biasing it more to oversteer. And Alan has installed the Sonett III’s floor shifter.

It all works. The V4 handles more like the production racer it almost is. Throttle steering is twice as pronounced and three times is fun, and while the triple is tapped out at 80, Allen’s V4 has more on top.

Saab built some 70 two-stroke Sonetts in 1967 before going to the V4, of which they made some 70 more. In ‘68 they made about 900, and 640 in ‘69 before switching to the Sonett III, with much less than the 3000 per year planned. Almost all came to the US.

If the Sonett to seems odd now, it was weird in the 60s, an instant cult car. Even Saab’s advertising called it “an expensive toy.” But it is so friendly, so delightful to toss around that it is hard to dislike once you have driven it. Perhaps the words of Sixten Sason, who designed the body for the 1955 Sonett car, describe it best of all. Those words gave the Sonett its name. Said Sixten, upon seeing the first Sonett, “so net den ar.” I couldn’t agree more.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.