Contemporary review/driving impressions originally published in European Car February 1993

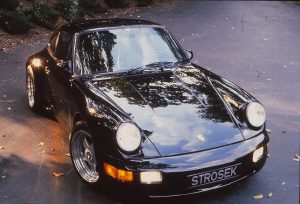

Lettered on the rear of the white Porsche is the word “Ultimate.” Rather heady and, one might suppose, a bit overwrought. Yet the braggadocio is not in the least undeserved. Because there might be more powerful Porsches, and certainly more dramatic body revisions, but it is very unlikely that there is a street-driven Porsche further out on the cutting-edge of technology than Marilyn Beddor’s – take a breath – Ruf Porsche 911 Carrera 4 Turbo EKS. With six-speed manual transmission. And data acquisition system.

Unless it’s Frank Beddor’s black Ruf Porsche ditto ditto ditto plus flared fenders and wider wheels and tires.

The two Ruf Porsches are a matched set for the all-wheel-drive husband and wife team who also oversees the Quattro Club for Audi enthusiasts. And don’t let the fact that the pair are grandparents fool you. The Beddors took their Porsches, fresh from Ruf’s Pfaffenhausen works, to the Silver State Classic and won first and second in class. Marilyn got the first. And nailed the 160 mile-per-hour top speed for which the car was teched right on the nose.

The car she drove is the one pictured. There’s not much, other than the Ruf wheels and the numbers and labels from the Silver State classic, to suggest that this is other than an ordinary Porsche. Second glances, however, will pick out the Ruf disc brake calipers and turbo wing, which doesn’t belong on a Carrera 4 – though the car is identified only by the Ruf logo on the rear deck – and the “Ultimate” lettering.

Most of the magic is hidden inside and underneath. It is indeed a Carrera 4, but the standard five-speed manual has been replaced with a Ruf six-speed, and the clutch pedal has been removed altogether to fit Rufs Fichtel & Sachs EHKS (or if you prefer the English, ECS).

This electronically actuated clutch was reviewed in european car in October 1991, but to recap, the system uses microprocessors and sensors to activate an otherwise standard clutch – there’s no clutch pedal – with an otherwise standard manual transmission. It’s more similar in concept to the Sportomatic system used by Porsche and Volkswagen in the early 70s, but thanks to the microchip much more sophisticated and even easier to use. Rather than the Sportomatic contact switch on the shift lever, EKS monitors the shift lever location and movement, as well as throttle pedal position, engine and transmission speed. The control unit, located in a box under the driver’s seat, controls the actuator which, in the Ruf Porsche, depresses a master clutch cylinder (the stock Porsche unit is replace) which hydraulically engages (or disengages, actually) the clutch as per usual. Altogether it weighs about 18 pounds.

The concept is simple, though it takes a lot of programming to make it work. The system must differentiate between casual around-town shifts and Johnny Lightning drag-race-for-turn-one gear banging. It does, varying clutch engagement rate on calculations by the electronic control unit. It also must protect the system against bone-headed driver errors, such as starting in third or higher gears, or downshifting into too low a gear for two high a speed. It does, by allowing the gear lever to go into that slot but barring clutch engagement. It also has to allow for different take-off requirements, which it does with a “ normal start” mode, a “kick-down” mode (with first gear engaged revs are allowed to rise to a preprogrammed level before the clutch engages rapidly), and “racing start” (which goes against your basic instincts by allowing you to hold desire revs in neutral and then pushing the lever into first gear while fully depressing the throttle pedal).

Driving this two-pedal Porsche takes some getting used to. In first gear, it motors away and simply as if it were equipped with an automatic. At least until it’s time to shift when, of course, the driver must move the gear lever. The temptation is to lift one’s left leg for the absent clutch pedal. That overcome, shifting is as easy as, well, just moving the lever to the next gear. The clutch uptake is smoother than the gear change of some automatic transmissions. It helps smoothness to match revs as much as possible, just as with a driver-operated clutch. In fact, we tried downshifting with a closed throttle, hoping to elicit a jerk when the clutch engaged. It won’t. Clutch engagement was gradual and the engine rose to match vehicle speed almost as if the computer had opened the throttle slightly. But there is no computer-control of the throttle. We also try to outshift it, but the EKS was quicker than even our best prestidigitation.

Price is 12,000 DM – about $7,800 – as an option in a Ruf conversion. It’s 16,000 DM – about $10,400 – as a kit, but installing the kit requires special training and equipment. Ruf’s Japanese importer, however, can do it now.

Also requiring some acclimatization – willingly acquired – was the Ruf turbocharged motor. More than the Carrera 4’s stock 247 hp, or even the 911 Turbo’s 315, the Ruf turbo produces 380 hp DIN at 5900 RPM. Maximum torque is 480 Nm at 5100 rpm. Ruf bumps the boost on a turbo spec motor (0.80 instead of 0.70 bar), fits special cams and intake manifold and modified ignition for the added power. The view under the rear deck is dominated by the intercooler, but be assured that there is an EPA-approved catalytic converter attached as well. Both cars are street legal.

We weren’t able to put a stopwatch on either, but Mickey’s arms were bent behind his back from the force of the acceleration in Marilyn’s car. It is said to be capable of over 190 mph. We saw 150 mph (well, 149 actually) on the main straight at Brainerd International Raceway. (Frank’s car, with the wide-body, is said to be capable of a mere 186 mph.)

A knurled knob below the dash is the only external evidence of another Ruf driveline trick, manually variable torque split for the all-wheel-drive system. Like the stock fully-automatic system, the Ruf awd as a base-line split of 31percent front, 69 percent rear. However, instead of Porsche’s system that electronically varies the torque split up to 50/50, Ruf controls it manually via the knob. A ZF rear differential with fixed 40% slip instead of Porsche standard variable slip is used at the rear. Ruf believes that the fixed ratio splits provide better handling than the variable electronic systems.

The cars are more than just drivetrain, however. Weight savings have been found to in replacing the electric windows and power locks with manual equivalents and otherwise lightening the doors. Racing mirrors replace the stock power adjustable mirrors and the rear window was filled with thin high-tension glass and the sunroof filled in, all for weight savings. A full-on roll cage – surprisingly discreet – probably more than offsets those gains but immeasurably adds to high-speed safety.

Ruf-tuned suspension was installed on both cars, lower and some 30 percent firmer than stock, with Ruf-spec Bilstein shocks. Three sets of 18-in. Ruf wheels were ordered for both cars, one for street and two for racing. For street use, the narrow body car’s wheels are 8-. and 9-in. .wide, respectively, mounted with 235/40ZR-18 and 265/35ZR-18 Michelins.

The wide-body car’s wheels are an inch wider with the same front tires and 285/35ZR 18 Michelins on the rear. For racing, both can have wheels 8.5 and 9.5 in wide front and rear with 235/35-18 and 265/45-18 Pirelli rubber respectively. Four-piston Ruf calipers replace the stock brake hardware, while larger diameter discs (322mm versus 298mm stock) are fitted up front.

An unusual feature of the Beddor’s Rufs are the data acquisition systems installed by RPM (Race & Performance Monitoring, Inc. Of Scarsdale, Arizona). The RPM onboard system records vehicle speed, engine RPM, lateral g force, steering angle, boost, oil temperature, braking (on or off) and “lap tracking” via a combination of RPM computer and IBM-compatible notebook computer strapped to the passenger side of the central tunnel. The data can be reviewed later or, in Marilyn’s car, can be read from a small color monitor mounted to the right side of the dash, and either digital or graphic display. The lap tracker records lap times from an infrared sensor mounted on the left front bumper that “reads” trackside reflector tape.

Additionally, on Marilyn’s car only, infrared sensors are installed to read tire temperature. The small sensors, which resemble a small penlight, are mounted in the wheel wells out of the line of fire of debris and are aimed at the tread surface. The system can be programmed to sound an alarm in case of excessive tire temperatures (or other warnings, such as overboost or high oil temperature). The computers, by the way, are easily removable for security purposes

Not surprisingly, the car is a delight to drive, whether on the road or on the track. On the latter it’s a handlin’ fool, gratifyingly easy to drive fast. Acceleration? Of course. Braking? Like a brick in the mud. And around corners is more predictable than rain on a washed car and a lot more fun. It’s almost impossible to put a wheel wrong: Back off and the line tightens, accelerate and the car runs wider through the turn. Cornering limits would send Mr. Newton back to the apple tree.

On the street, Marilyn’s C4 is a rocket. Under boost there’s a loud hiss, and a shift or two later the speedometer is pointing to 120 and your driver’s license is more a risk than anywhere this side of a shredder.

But it all boils down to performance, technology, and flat-out fun. The Beddors matched set of Porsches provide each in seemingly unbounded quantities. Which explains why “Ultimate” is less bragging that it is a mere statement of fact.

it’s so nice to see the actual progress of these RUF machines as complete packages

with engineering art capable of the long standing sports car tradition of drive to track

and then race and drive home…