History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek May 5, 1995

When Eugene Casaroll, owner of Dual Motors, decided to go into the car business, he wanted to make sure his cars wound up in the hands of all the right people. He reportedly used the Social Register to screen the 100 buyers of his first Dual-Ghia, an adaptation of the Dodge Firearrow show car. Casaroll was a Daddy Warbucks who had made his fortune during World War II selling dual-engined trucks to the Air Force – hence the “Dual” name.

The Dual-Ghia thing was little more than a hobby. That the first one lost money was a disappointment, but Casaroll enjoyed calling the shots. So he asked Ghia to build him a second model for display at the 1958 New York Auto Show.

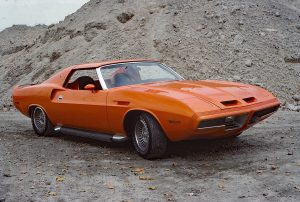

This car, the Dual-Ghia 400, was also a direct adaptation of a Chrysler/Ghia dream car, a product of that era’s peculiar push me/pull you match between Virgil Exner’s Chrysler styling studios and the Ghia coachworks in Turin. The 400 copied the Chrysler Dart, which expanded the themes from Ghia’s non-running Gilda show car to Imperial dimensions.

The 400’s chassis was that of the mighty 1957 Chrysler 300C (the first Dual-Ghia used a cut-down Dodge convertible chassis). The 300C’s 392-cid Hemi with the optional power pack – 10.0:1 compression ratio and dual four-barrel carburetors – was matched to Chrysler’s three-speed Torqueflite automatic transmission. The 400’s engine had been built on Chrysler’s industrial engine line, and a combination of industrial heavy-duty bits and high-performance pieces made it slightly more powerful than the standard 390-hp unit.

In the transition from Dart to Dual-Ghia, the headlamps and grille were altered, and the shape of the oval front bumper was modified. A dummy scoop was added to the hood. The Dart’s razor-thin tail fins were fattened on the 400 to incorporate lamps similar to those of the 1957 Chrysler. Differences between the Dart and the 400 really don’t stand out unless you put the cars side-by-side. Unfortunately, that’s no longer possible. The Dart was cannibalized for the construction of another show car.

Although Casaroll opted not to manufacture the 400, his show car met a kinder fate than did the Dart. At its New York debut, the 400 attracted at least two ardent admirers. One, Fred Kantor, was still a kid who could do no more than promise himself that one day he would own the car. The second, Alex Freeman, owner of a Newark area machine shop, offered Casaroll a blank check. Casaroll probably thought he was calling Freeman’s bluff when he demanded the full sale price of $15,000 upfront, promising delivery only after the car spent a year on the show circuit. Except Freeman wasn’t bluffing.

After Freeman took title, the car was refinished at Dual Motors expense. The typically heavy layer of Italian surface finish had cracked the paint. Freeman had the car brought back almost to its original black on pastel yellow. He also ordered spare front and rear bumpers made from the original bucks ($155, no chrome). He drove the car regularly, totaling 38,000 miles by 1977.

In 1970, Fred Kantor saw the car advertised in the New York Times, but the price was too high for him. Seven years later, however, Kantor learned that Freeman again was trying to sell the car. Within three hours, it was his. Freeman had maintained the car well, despite using it (he did install the spare front bumper), and Cantor decided to leave it in original, unrestored condition. Today, there are a few small dings in the bodywork. Although the interior leather is in great shape, the padding beneath sags. The car is mechanically like new – Kantor owns a Boonton, N.J., restoration parts company that bears his name.

Upon settling into the driver’s seat, one is confronted with the massive steering wheel of the era. There are no stalks coming off the steering column. The Torqueflite’s pushbutton controls (no park) are dashboard mounted, and the turn indicator switch resides on the center console, a small twist lever that self-cancels and also has a timer.

The cowl is high and the car’s dimensions are imposing to a driver accustomed to modern, smaller sizes. It’s like driving a chopped and channeled Suburban from the second row of seats, except that the period power steering delivers no feel and has more play in it than an elementary school recess period.

The Hemi bellows satisfactorily, but you would be well-advised to have a lot of empty space to run in before seeking the stalemate between Cd and hp.

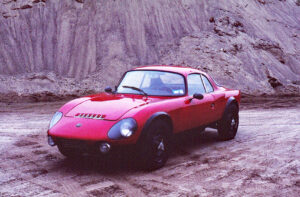

Though he billed the 400 as a prototype, Casaroll didn’t order a second copy. Production of the original Dual-Ghia was done, and the next prototype, the L6.4, didn’t appear until August 1960. It shared style features with the original Dual-Ghia, not with the 400.

A testament to the power of design to trigger emotional responses, the Dual-Ghia 400 survives thanks to Freeman and Kantor, both of whom were struck by the sight of a car at the New York Auto Show.

Fred Kanter and his brother Dan is still in business, selling restoration parts for Packards, perhaps the world’s greatest collection of new-old-stock Packard parts in the world, along with parts for old Buicks, Kaisers, Nashes, Edsels, Hudsons… He also created N2A Motors, which allows a purchaser to choose from the front, interiors and rear ends replicas of the ’57, ’58 and ’59 Chevrolets and apply them to a “no two alike” combination. And he’s also one of the premier collectors of concept cars, of which the Dual-Ghia Prototype is one.

very cool to see the pictures and great article my uncle is alex freeman. it is great to see the car is still around. well preserved .

For me the “discovery” of this car pales in comparison to discovering this website!

Thank you, Carbuzzard.

RB