History originally published in Sport Compact Car December 1996

The Datsun 240Z is famous for its design, but nothing comes out of nowhere and that’s as true for the Z-car as it is anything else. The obvious predecessor to the Z is the 1500/1600/2000 Datsun roadster (read more about the 2000 roadster here) series, and indeed the Fairlady name was used, at least at home, for both. And true, both were sports cars and both were built on the same assembly line until the 240Z’s popularity spelled doom for the roadster as Nissan craved production capability.

But as much as the 240Z was a functional replacement for the roadsters, the Z-cars predecessor for design was a car never brought to the United States in fact even was a bust in Japan. This was in 1965 Sylvia.

The Sylvia was to be a companion for the roadster, a grand touring version. But rather than slap a hardtop on the open car, a quick and dirty solution, Nissan planned entirely new sheet metal. The separate box rail with X-member frame would be kept, however, along with the engine, running gear and suspension. But the new GT would have a completely new look.

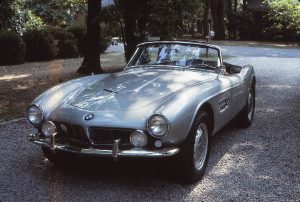

As luck would have it, Albecht Goertz, a German-born, New York-based industrial designer, had decided that Japan needed his talents as a car designer. Nissan in particular had a number of bad Japanifications of European and American exteriors; some other Japanese carmakers had already utilized the talents of Italy’s famous designers. Goertz had BMW’s 503 and the fabulous BMW 507 (read more BMW 507 here) to his credit. So when Goertz knocked on Nissan’s door—and knocked, knocked and knocked again—he was welcomed to work on the new GT program.

Goertz later said that, with virtually no design tradition, Nissan’s designers lacked basic design skills. It was something they had never been taught. Cars were often assembled from disparate parts, a design by committee approach with each committee member not speaking to the other. Goertz showed the designers how to design a complete car – and taught them not to look at a car just from its good angles. A more immediate problem was that most of the design crew didn’t own cars. Which in the early ‘60s were still too expensive for the typical worker to own. They were trying to design something they had never used! And worse, the standard for occupant space was a 5’8” tall cardboard cutout (contrary to Goertz request for a 6’5” standard for American sales).

Working with these constraints, however, Goertz’s contributions yielded a striking two-place coupe, European in tenor with broad sweeping surfaces instead of the typically festooned, busy and over-ornamented Japanese styling. At a glance it could be a Lancia. The leading edge of the hood curved unbroken to form a single beltline from nose to tail, interrupted only by a doorhandle integrated into the shape. A discrete concave element ran from the top of the front fender up the front of the C-pillar. Quad headlamps flanked an elegant grille of fine horizontal slats. It was a distinctively handsome car.

Its model designation was CSP-311, for a coupe version of the SP-311 roadster, but when Nissan debuted it at the Tokyo auto show late in 1964, it drew a crowd. Likewise at New York in the spring of 1965, Road & Track said, “completely original and very well finished. It offers a combination of proven chassis and engine wrapped in an attractive package.” Car and Driver went relatively nuts, calling it “one of the most ogled exhibits.” Thus emboldened, Nissan gave Silvia a tryout in the States. Equipped with the 1.6-liter pushrod four of the 1600 roadster, the coupe gave similar performance, its top speed three mph less than the roadster’s 106 mph. The Silvia, however, was just too small. Designed closely around the roadster’s dimensions, the coupe’s interior was too narrow, the steering wheel barely providing clearance between the wheel, the cushion and the door panel. The steel roof, despite Goertz’s airy greenhouse, proved claustrophobic in a way that a lowered roadster top never could.

Advised against it, Nissan decided not to import the Silvia into the United States. It was a wise decision. Even the Japanese, who had been enthusiastic about the prototype, failed to buy in droves and the model went out of production in 1968. Goertz, however, had gone on to another project at Nissan, this for a true two-seat sports car. Through a complicated chain of events, that car’s engine, designed by Yamaha, wound up in the Toyota 2000 GT and Goertz’s body design, albeit modified, eventually became the Datsun 240Z with Nissans 2.4-liter six.

Too tiny to be successful in its own right, the Silvia was critical to the very existence of the Z. Even if it weren’t so good-looking – and it was – it could be remembered as the key to the 240Z’s success.

Who gets credit for the design? If you ask Goertz, as I did in one of several interviews, it was he. The official word from Nissan is, “The exterior and interior were designed by Nissan internal designers (K. Kimura & F. Yoshida) with advice from then-consultant A. Goertz.”

According to the Nissan Heritage Collecdion, “As few as approximately 550 units were built for 4 years because nearly seamless bodywork and elegant interior on chassis for Datsun Fairlady 1600 SP311 were semi-handmade. It was known as the pioneer of sports coupe and the first highway police car in Japan.”

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.