History originally published in AutoWeek December 16, 1985

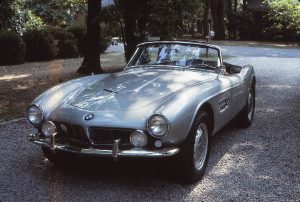

This is a shape, profoundly sensual, utterly female. It is sublime in efficiency, knowledgeable of what must be known, simple and spare like some great rolling Bauhaus woman, a supple stylization of the female form.

It has hips. Viewed from above, it narrows from the shoulders of the front fenders and then widens again at the flanks where it should be wide. The hood line curves like the nape of the neck, and the front fenders swell in contour that is unmistakably mammary, the headlamp placement is unerringly true. Let them speak of the sensuality of the pen of the Italian designers, of the methodical Teutonic bent. This automobile will put it all to lie.

It is indeed German. A man named Hoover came to BMW as a stylist and an aerodynamicist and in the middle of 1938 drew up this car. It was the prototype, the before the first, of the three coupes and three spiders that ran to such convincing victory in the 1940 Mille Miglia.

The fact that so much is known today, and even that the car exists, can be attributed largely to two men. One is Jim Proffit, a bearded oversized teddy bear of a man who restored the car, pursuing it from a photograph in a friend’s collection to the realization of the vehicle itself, in storage on blocks, with Triumph brakes and a Corvette engine and bastardized headlights mounted on flat panels where the curve of the fender used to be and huge holes cut in the side panel for the side pipes to exit. It had been converted earlier – and more artfully – to road equipment, with the top and so forth neatly brazed onto the chassis. Proffit suspects this latter was the work of Alex von Falkenhausen, who had been chief of engineering at BMW before the war and in 1946 established AFM (for Alexander v. Falkenhausen Munchen) for the purpose of building and racing automobiles. Which may explain the AFM grill on the car when Proffit found it. In may also explain how von Falkenhausen, when Proffit had the car in Europe for the first rerunning of the Mille Miglia, walked over to the car, took a long look at it and walked away, refusing to say anything.

What is known about the car rest largely with a Dr. Simon, who has performed comprehensive research on the BMW 328. It was Dr. Simon who discovered the drawings of this car. But the car itself is so obscure that the factory didn’t know that they had put it together. There is no racing history for it. In fact, nobody knew anything about the car except that its construction was correct, a BMW-patented technique of using tubing and strapping to form the contours of the body and then stretching and crimping the body over it. Exactly – precisely – what it is still something of a question, but whatever it is, it is authentic.

Most likely it was a developmental car. The way it was originally built the differential couldn’t be removed from the car, and even just changing the tires was difficult due to the cut of the wheel arches. Even the tire to back-of-the-headlight clearance was inadequate. So the car, having proved the basic concept but unraceable as it was, was probably relegated to sitting under a tarp in the back of who knows where until whatever happened to it happened to it.

Coming to this country probably in the hands of a returning GI, it then went through several owners and several iterations of form before being rescued by Proffit (one of the terms being that the Corvette engine not be part of the package, much to Proffit’s mock disgust). The original body had been much too abused (including an accident while unloading the car at Proffit’s shop) to warrant saving, so Proffit had another made for the chassis.

It was constructed using the original methods but changing details were BMW would have had to have made them, such as reducing the wheel arches slightly to facilitate wheel removal or carefully adding an inch to the front of the body to allow for clearance between the front tires and the back of the headlights. The car uses heavy wood plates around the doors with steel straps holding them together rather than dove joints and dowlings and so forth, surely not as light as it could be or would be. An interdepartmental memo of the time addresses weight, so we know that the factory was weight as well as aerodynamically conscious.

Proffit was also able to obtain original-style factory wheels for the car. There were actually two styles of wheels made by the factory, with integral brake drums or without. Proffit’s roadster has the latter. Whether they were factory built is impossible to tell, however, as after the war an Englishman named Willis ended up with the patterns for the wheels. So these particular wheels may be factory or they may be Willis’ wheels. Either way, the rims measure 16×3.5 inches, on which Proffit has mounted Dunlop 5.50×16 nylon racing tires. (The factory competition wheels are 4 inches wide, but also 17 inches in diameter, and naturally are very hard to find tires for).

The engine is Fritz Fiedler’s 2.0-liter six with its incredibly complex up, over and around valvetrain that turned the plain pushrod engine into a high revving hemi-head performer. (The design was actually good enough that Bristol continued to use it into the early ‘60s, incidentally powering quite a few ACs to various championships). It is essentially stock (though with enhanced oiling for that busy valvetrain) but has been measured at 140 bhp on a chassis dyno, and that with a 3.44 final drive.

The car will run 5750 rpm – or 130 mph – in top gear, a testament to Herr Hoover’s aerodynamic work. In fact, when tunnel test run on the BMW 328 Mille Miglia roadster with belly pan and spats fitted yielded a .32 Cd. (If that’s impressive – it’s the same as Porsche’s 924S – the Mille Miglia coupes checked in at .28, this at a time when Mercedes were pushing around half the air over Germany before them). And with weight at 1,480 pounds wet and ready to race the acceleration should be more than startling for a car of late 30’s design.

Ready-to-race weight is a known factor because that is what Jim Proffit has done with his rarer than rare car. Obviously not one to sequester the automobile in some dusty museum, Proffit took the car, as mentioned, to Europe for the inaugural Mille Miglia re-run with none other than AutoWeek Associate Publisher and Editorial Director Dick Hinson along. The car is now owned by Joliet, Illinois, BMW dealer Bill Jacobs, who ran it at the 1985 BMW Vintage Fall Festival at Lime Rock, which is where I was asked to photograph and drive the car for AutoWeek (it’s a dirty job, etc.). The only catch was that my driving was to be done after the racing was over, and when it was after more than half the lap of the third and final race for the group had been completed when hard the last word – aargh – the voluptuous white form was missing from the pack. Jacobs had felt the rear end go funny and pulled it in. There would be no more driving the Mille Miglia until the rear end could be inspected and repaired.

Some, not restrained by the need to maintain domestic tranquility, might comment on how like a woman, etc. Another, more circumspect, will only remark that Jim Proffit’s elaborations on the sweet nature of the car’s handling were only the more frustrating for not having experienced it. This rare and mysterious automobile was at the forefront of designs of its era, and is equal would be more than a World War and a decade in coming.

I received a letter–back when people still set pen to paper–criticizing my rather florid description of the contours of the BMW 328 Mille Miglia Prototype, particularly the anatomical references. It’s a metaphor, a simile, all figures of speech. I have a poetic license and I’m willing to use it. And that’s how I saw it.

The BMW 328’s six cylinder engine continued after World War II powering Bristol automobiles (before Bristol began using Chrysler V-8‘s) and others, including the AC Ace/Aceca and Arnolt-Bristol.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.