History originally published in AutoWeek, December 27, 1982

For some, a Rolls is to ostentatious. For some, a jaguar is too common and flashy. Mercedes or BMW, too, well, German. Italian cars are simply too exotic. Even a Bentley is too obvious. For these people, however, there is Bristol.

Bristol is a carmaker for a very few people. Production is about 150 automobiles per year, two or three per week. Every one is specially ordered, every one is custom tailored, built to the highest craftsmanship and most stringent aircraft standards. Bristol’s have not been, however, high points in automotive styling, even in the estimation of Bristol enthusiasts.

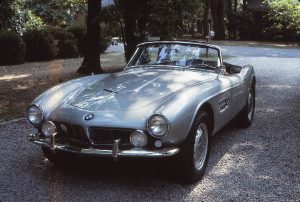

It has certainly been that way since Bristol began making cars in 1946. The Bristol Aeroplane Co. added automobiles to its postwar plans which it did not see including enough aircraft production for solvency. After the Car Division’s own prototype had crashed rather conclusively – the radial engine mounted high in the rear made it handle rather like a sailboat with a lead mast – Bristol turn to the designs of pre-war BMWs to shorten development time for a production-ready vehicle.

It was fortuitous decision, for Bristol has continued to rely on the 6.5-inch deep box section frame even up until today, with changes in detail only. The two-liter BMW engine served until the early 60s, only then failing to provide the performance differential expected over more common, less expensive automobiles. Bristol was loath to change, but even highly tuned, the inline-six couldn’t move the solid (read “on the heavy side”) cars fast enough.

There was an in-house project to replace the aging engine, but the beautiful twin-cam six was scuttled because of financial need on the part of the aircraft division. As a result, there would be no alternative but to go outside for an engine. Logic supported an American V-8 – technologically unexciting, but possessing an excellent power-to-weight ratio and a compact layout. After due consideration, the Chrysler 318 with Torqueflite automatic transmission was chosen

Actually, it wasn’t the 318, but the Chrysler of Canada’s 313, to keep it within the Commonwealth, one supposes. Chrysler built a unique version of the engine for Bristol, with the Hemi head, a high-lift camshaft with mechanical lifters replacing the hydraulics, a four-barrel Carter carburetor and a larger capacity oil pan. Once at Filton, however, Bristol virtually rebuilt the engine to its exacting specifications.

The engine was then eased into the bay of the Bristol 407 for the 1961 model year – starting a tradition which would continue to the present. The 407 was actually a transition model, a 406 with a V-8. Both these models stay true to the aircraft-inspired styling that began with the 404 in 1953, when that model replaced the BMW-like 400 through 403 cars.

The Bristol 408 came in 1963. It was an example of how much how and little a car could change. Gone was the streamlined snout, replaced with by rectangular cavern housing an extra pair of lamps and of Venetian blinds grille. The headlamps and turn indicators were mounted on vertical slabs, and the greenhouse, though actually lower, was squared off for more rear seat headroom.

Underneath, however, it was still all Bristol. The welded steel box section frame remain, and the 408 continued the double wishbone and coil front suspension of the 407 inaugurated in lieu of the earlier transverse lower leaf arrangement. At the rear was the same live axle on longitudinal torsion bars inherited from BMW and still used today. Dunlop disc brakes were still at all four corners, and a 408 did not break the Bristol tradition of locating the battery and various electrics under a door in the fender on the passenger side and a spare tire on the other. The Chrysler 313 was continued for all of the 408’stwo-year model run, except on the final few cars. These, known as the 408 Mark 2, received a 318-CID version of the motor and a torqueflite updated to include park on the quadrant, i.e., another push button on the dash.

Of the 300 or so Bristol 408 made, most were destined to remain at home in Great Britain. Few went abroad, and fewer still were originally built for foreign destinations. Thus, it was a rare indeed 408 that Kenneth Iskow found languishing on a Toyota dealer’s used car lot. No history was available, no one knew whether the odometer had been turned over once, twice, or maybe not at all. But it did have left-hand drive. And it was obvious that it had been neglected.

Iskow did what was necessary to make the car truly roadworthy again. Fortunately, the aluminum body work at survived unscathed, but the engine and transmissions were more history than current events. They yielded to a cooking two-barrel 318 and Torqueflite. Not original, but hopefully the folks at Filton would understand. They did, after all, supply the specially calibrated Konis to replace the Armstrong originals. The Armstrong shocks in the rear were special “Selectaride” units with variable damping adjustable by a knob on the dash. The shocks were clever in concept, but disappointing in reliability, and Iskow’s were completely worn out.

Otherwise, the car is stock all the way to the drooping-mustache spoked steering wheel. The steering wheel is unusual, looking like a cross between a pilot’s yoke and an automotive steerer, but does afford an unobstructed view of the seven gauges neatly clustered and mounted on a walnut veneer. The interior is a roomy place, and it’s as comfy as going home. It’s a true four-seater, with ample room for a pair of backseat passengers. The only trouble is getting in. The 408 is a two door, and the portals aren’t all that big.

The Bristol maintains that homelike feeling on the road, too. It’s quiet. The engine doesn’t intrude, being audible only if you listen for it. The ride is syrupy: smooth and sticky. Bristol avoided the “pillow soft” feel of which Detroit was so enamored, instead achieving “firm but gentle.” Much of the credit must go to the massive frame which by his strength allows no chassis shake or shudder, much less chassis flex, even a rough roads.

If the ride is house -like, though, so is the steering. At low speeds it will build shoulders and biceps faster than Charles Atlas, and although the heaviness diminishes with speed, it is replaced by a combination of stiction and numbness. Bristol hadn’t completely sorted out the new double wishbone suspension on the 408, the 409 was reportedly much improved.

It seems to be on rolling two-lane highways that the Bristol 48 is most at home. The 318 in Iskow’s 408 is still able to move the 3,500 pound car rather smartly (though it probably won’t turn 16.1-second quarter miles like the original engine would when new) and the steering provides the best feel when turning. This just the thing, say, for an antique-hunting jaunt into the country. The trunk – big enough for a Moscow family to call home – is also big enough for luggage for four and a whole bunch of old junk. Of course, it would take very special people to appreciate the Bristol, both in attitude and in checking account. The UK price for a ‘64 like Iskow’s was £4,461 pounds, that in a time when a pound sterling cost between three dollars and four dollars – and for a car of questionable aesthetics.

But then, it isn’t really all that bad looking, especially from the right angles. And there is the comfort factor, not the mention the “knock-down-stone-walls” crash safety Bristol enthusiast so enjoy discussing…

It’s a car which seemingly takes a while to get to know – and appreciate

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.