History/driving imressions originally published in AutoWeek October 20, 1986

Grand routier. It has that certain sound even on paper, without even being spoken. There can be no doubt that it is French, nor of its meaning, even for someone who doesn’t know the language and even if there is no direct translation into English. This was a great road car of France.

This was Bugatti, this, Delage, Delahaye and Hotchkiss. This too was Talbot Lago.

And all of them, each and every one, gone.

Things happened. The economy changed, people came and went, and the times were different. Mistakes were made in management. The war, of course, devastated France, and the French government did its part with a heavy tax on automobiles with engines larger than 2.8 liters. And it’s difficult to build a great road car without a great engine.

Talbot Lago had learned this with the 2.5-liter coupe of 1955, of which some 40 were built. Its four-cylinder—derived from the fabled late-‘40’s Grand Prix six that beat Ferraris with reliability and fuel economy—was rough and underpowered, hardly up the standards of pre-war 4.5-liter coupes with bodies by Saoutchik or Figoni and Falaschi or even the post-war Lago Record with pleasant styling and 170 horsepower.

Thus Tony Lago, who had acquired the French side of the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq combine when it collapsed in 1935, found Talbot Lago in difficulty some 20 years later, caught between high taxation of his cars and his own indulgence in racing. Lago struggled to meet payroll and suppliers weren’t being paid, even the foundry that supplied the engine blocks.

However, salvation, if seemed, lay no further than the other side of the Atlantic. Americans were rich and the French government would assist firms that exported.

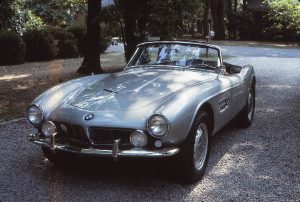

It was a goal Lago pursued unabashedly with a car designed specifically for America. For the first time from Talbot Lago, left-hand drive was available. Only two cars, those bound for England, had right-hand drive. A V-8, from BMW, was under the hood (more because the foundry refused to cast more blocks than from choice). And for a name, Tony Lago chose “America.”

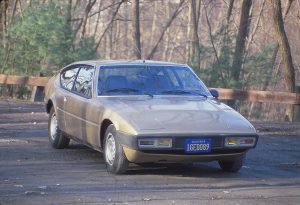

It was a beautiful car, shaped in the post-war Talbot tradition and unmistakably European, designed by Carlo Deflaisse. It was one of the more successful attempts to merge a classic pre-war grille with post-war lines. The car was distinctly feminine, especially from the rear, with a coquettish wedge of a rear window and delicate, inward leaning fins that terminate in button taillights. The body was steel, but the hood, trunk lid and even the non-removable roof were made of fiberglass.

The chassis was fairly conventional, with a live rear axle on leaf springs and front suspension of top control arms with a lower transverse leaf. Sixteen-inch wire wheels revealed huge finned aluminum brake drums. An all-synchro four-speed ZF transmission was mated to the BMW V8.

If providing an engine to a direct competitor seems odd, like a Chevy small block in a Mustang, it should be remembered that the German firm was itself struggling, and a sale was a sale. The BMW 507 lost money even at the then lofty price of $10,500. The Lago America was cheaper but still an if-you-have-to-ask $6,995. So despite the fact that Lago had tooled up for a relatively large production run, only 12 cars with BMW engines were built and all were exported. It was at this point in 1959 that Tony Lago sold his company to Simca, likely never having paid BMW.

Who knows what Simca executives thought they were getting, but what they got was an exotic automobile firm profoundly in debt, likely owning more than they had paid for the company. Tony Lago had pulled a fast one, concealing that debt—apparently Simca never asked—until the purchase. Simca elected to shut down Talbo Lago rather than spend a decade repaying the debts.

Yet there was the matter of work in progress, which Simca allowed to continue with supplies on hand. That didn’t include BMW engines. Simca had, however, as a result of its purchase of Ford of France a few years before, a V-8 of its own, the old flathead Ford 60. Dressed with a pair of Stromberg carburetors and bolted to the ZF four-speed, it made a strong if somewhat common powerplant.

There were enough parts for five more cars, all Ford powered and all remained in France, at least until the mid-1980s. One car, if rumors are true, had belonged to a French count and possibly Bridget Bardot, though there’s no proof of either, although it is known that it was in a museum for ten years. More recently it was sold to Ed Waterman of Motorcar Gallery, Ft. Lauderdale, Fla.

Whoever the previous owners, the Talbot Lago America is fun to drive. There’s no tach—supposedly they ran out—and instrumentation is limited to speedo, engine temp, amp and fuel gauges, and an oil pressure light. The clutch is heavy—fortunately the travel required is minimal—but the shifter is smooth and precise as a machinist’s business card.

The steering wheel is big: The leverage is needed at low speeds as the car feels heavy despite its 2,640 pound curb weight. The heaviness, to coin a phrase, disappears with speed and on a winding road comes into its own, the Ford engine’s exhaust rumbling, the Strombergs hissing, and wind whistling around the door tops. The car corners neutral and flat—if somewhat stiff—and winding the flathead is excuse enough to slide the ZF into another gear.

The building of number 15005 signified more than the end of the model. Of all the great pre-war French marques, Talbot Lago was the last to die. Lago America 15005 was the last production Talbot Lago ever made. It was an era finished.

Tony Lago died in 1960. They say it was a broken heart.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.