History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek April 15, 1985

The year was 1968. Both the Dodge Charger and the Ford Fairlane had been freshly rebodied. The Chargers swoopy new styling replaced the angular tacked-on fastback of its original incarnation, while the Fairlane got a fastback version to go along with the formal notchback sedans. It promised an interesting year for NASCAR competition, if only to see how the new aerodynamics would shake things up. The ‘67 season had not been good for Ford. The first meeting of the makes was at Daytona, and it marked an immediate change in the fortunes for Ford. Instead of the also-rans of the ‘67 season, the Fairlane Torinos and sibling Mercury Cyclones were at least 6 miles an hour faster in qualifying than the fastest Chargers. Only Richard Petty was able to break the Ford stranglehold, and only occasionally in a ‘68 Plymouth Roadrunner with special aerodynamic attention. It showed in the results as well: Cale Yarborough took the checkered in a Mercury, and FoMoCo products grabbed four of the top five places.

Now, NASCAR stockers had never been known for their aerodynamics – even the race queens were more, uh, streamlined – but that was where the answer lay for Chrysler.

The problem was in the Charger’s recessed grille and rear window, the former acted like a parachute and the latter, as speed, tried to suck half the state of Georgia along in its wake.

What, then, about a special run of Chargers with flush grilles and fastback rears? Only 500 would be needed for homologation. Along about June of ‘68, Creative Industries, a Detroit shop that since 1953 had been doing things that the automotive industry couldn’t or wouldn’t do for itself (and is still at it today, making LeBaron woodies for Chrysler), began the task of preparing for production a special Charger along lines laid out by Chrysler.

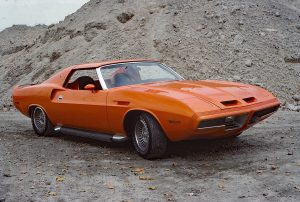

In August 1968, production began. Completed Chargers coming off the production line were trucked to Creative Industries for conversion to what would be known as the ‘69 Charger 500, different from the regular Charger in three ways. First was the grille. Instead of the recessed grille with a stylish retractable headlights, the 500 got a specially made stamped grille with fully exposed lamps. The second change was a turbulence-reducing sheet-metal “sleeve” over the A-pillar. The third was the replacement of the recessed rear window with new sheet metal between the “sail fins” at the rear of the roof and a special piece of glass for the rear window.

The result was a car that from the front looked cheaper than the standard issue and from the rear looked wildly impractical: The tiny trunk lid, made necessary by the fastback roof, meant that although the 500’s trunk was just is big, you would need a funnel to put anything into it. At least one newspaper scribe wondered whether they were going to sell very many.

Of course, that wasn’t the point. The purpose of the car was to win races. Those changes, though unstylish and impractical, in track testing demonstrated improvement of from 3 to 7 miles per hour. At 17 hp per mph gained – the generally accepted factor at the time – the alterations were well worth the effort. But it must not have been enough for the folks at Chrysler, or perhaps the case was, “if some is good, then more is better,” because plans were a afoot for an even more slippery Charger, the Daytona, with a pointed nosecone and clothesline spoiler. The 500 was discontinued at the end of 1968, and replaced immediately by the Daytona, and for Plymouth, the Superbird.

Still there was the matter of production for homologation purposes. How many were built in those few months is not clear. Several numbers have been bandied about, one of which is 500, the line being that Dodge made exactly the homologation number and quit. Another is 548. The third, and most probable, is 392. One problem is that both the ‘69 500 and the ‘69 Daytona shared the body code XX29. One set of records show that 392 XX29s were shipped in the 1969 model year, and another record indicates that 501 Daytonas were produced but doesn’t mention 500s at all. We recently interviewed Vern Koppin of Creative Industries, who worked for the 500 project, and he confirmed that less than 500 were made, although he was not able to declare precisely how many. So, barring evidence to the contrary, 392 it is.

Whatever, Ford was ready for the Charger 500 at the ‘69 Daytona 500 with a special re-schnozzed Fairlane, the Talladega. The hemi-powered 500 was a match for the 427 Fords at Daytona, however, and though Charlie Glotzbach’s Dodge came in second to Leroy Yarborough’s Talladega, it took the last corner pass to do it. But Ford’s one-wo punch included the Boss 429, which was ready and winning by the Atlanta 500. In fact, the Boss, in either the Talladega or the similarly streamlined Mercury Spoiler version, had things pretty much its way on the superspeedways until September 14, when Richard Brickhouse won the Talladega 500 in a Charger Daytona. The Daytona had been first shown to the world on April 13, but was not homologated until the September race, so it was up to the Charger 500 to uphold Chrysler’s honor – despite the fact that it was never produced homologating numbers. In case you’re wondering, Ford won the manufacturer’s championship for ‘69.

We may be reasonably sure that 392 Charger 500’s were produced, but how many went to the races is uncertain. The 500 with the lowest-known existing serial number now belongs to Hemi-enthusiast Mike Russo of Memphis, New York. Mike bought his 500 off a used-car lot in Albany, New York, in 1970, and he confesses that at the time of his purchase he had no idea how rare his car was, or even that it was anything but a standard Charger. It was not until fellow enthusiasts started pointing out the differences that Mike got curious, his first reaction being one of regret – he felt he had bought a cheap “stripper” version of the car. But when Dodge parts managers started going “Whuzzat?” to his request for Charger 500 parts, and when he found a vacuum canister and several miles of vacuum hose for the retractable headlights he never had, he began to suspect that he had something rare indeed. Several letters later, Russo knew exactly what he had: It was the press car for Chrysler’s PR office in New York, and the only such animal in the country with a Hemi and a four-speed. To be sure there were other Hemi’s and four speeds, but not for the press.

Having survived its share of journalistic abuse, the car was sold to a bank in Boston, and from there it went to an auto auction and thence to Turnpike Auto Sales. Russo bought the car on July 1, 1970, and has owned it ever since. Russo’s car, with the “SE” (for Special Edition) package, is well optioned – all of the normal production line options were available on the 500 – but, unlike a number of 500s sold through more normal procedures, it happily escaped a dealer-installed vinyl roof. It does have the 426 Hemi (the other choice was the 440 “wedge”) and it has the white “bumblebee” stripe that was de rigueur for Mopar performance vehicles in the late 60s, setting off its intense red paint. What it doesn’t have is that vacuum canister – which Russo now greatly regrets having removed in the interest of weight savings (in a 3500-plus-pound car!).

Settling in behind the wheel of Russo’s 500 reminds one of how the world has changed in 15 years. The doors are big and heavy and that broad expanse of hood seems to be the flattest acreage to be found in central New York. Nothing in the interior dispels the aura of size. Even the shifter has a dogleg in it so that the driver can reach it without a change in ZIP Codes. And remember, folks, this is an intermediate-sized car.

The big car feeling never goes away, even at speed, and though the car remains relatively flat through corners, it ain’t no Lotus Elan. So just pump those hemispherical combustion chambers full of vaporized fossil fuel, sit back and enjoy a ride on 425 horces.

Actually, the Hemi feels soft – if that can be believed – but it’s a result of a high 4000-RPM torque peak. Making maximum performance even more difficult is one of the tackiest tachs ever made. The needle, sweeping around the clock in the center of the gauge (time to shift?), has to be running several thousand RPM ahead of the engine. Not willing to scatter Russo’s brontomotor over a goodly portion of the Empire State, I shift early and missed the best part of the Hemi’s power band. But believe Russo, the package works. He has genuine dragstrip time slips in the 14s. If that’s not impressive, take your stock ride out to the U.S. Whatever Dragway and try to do better.

It’s a ride into anonymity, however. The Charger 500 goes largely unrecognized, a chapter mostly forgotten, swallowed up in ’69 by the power of Ford’s Boss 429 and in ‘70 by the aerodynamics of Chrysler’s own Daytona and Superbird. Even Dodge sullied its reputation by building “Charger 500s” in ‘70 and ‘71 that shared nothing with the ‘69s but the name. But to the knowledgeable few, those who remember, the 500 will remain as aerodynamic’s missing link.

Owner Mike Russo’s research on the provenance of his Charger 500 as a press fleet car included following up on minor body repairs. Autowriter Ro McGonegal told Mike that indeed, he was driving the 500 when a car pulled out from a side alley and hit the car in the side. I followed up with Ro, and indeed, the story checked out. Not only was the Mike’s car the unique four-speed press fleet 1969 Dodge Charger 500, it was the unique four-speed press fleet 1969 Dodge Charger 500 with authentic body repairs. That’s truly one-of-a-kind.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.