Originally published in Road & Track’s Exotic Car Quarterly, Fall 1990

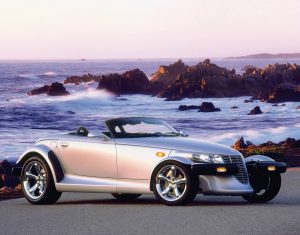

Evans Series 1; John Matras photos

Is this how Colin Chapman started out? Did Ferry Porsche spend most of his time meeting government regulations? Whould Enzo Ferrari have succeeded if he had to deal with government regulations stacked 10 phonebooks high?

Indeed, John Evans said if he had known what he was getting into he probably never would’ve started. Yet now he’s in too deep, too far to turn back. His Evans series 1 meets every applicable federal regulation, his prototype is a living, fire breathing thing and he’s ready to make Scottdale, Georgia, another Hethel, a second Stuttgart, the Maranello the mid-South. All he needs now is a buyer, an order and, most of all, deposit on the first production model from Evans automobiles.

This car building business is an expensive proposition. The 35 year old Evans spent his life savings on it and sold his rental properties to buy parts, laboratory time and the midsection of the Argo JM19 that Jim Downey raced at Daytona and used it to win his class at Sebring. But the story goes back to a boy who grew up loving cars, whose mother would drive him around parking lot so he could look at cars’ exhaust pipes which in that long-ago day came through bumpers and were a distinctive part of a car’s styling. That same boy earned the money to buy a Bugeye Sprite and then an Alfa Giulietta before he was old enough to drive.

A dream of designing cars – and building them – yielded to a self-admitted lack of talent and a chemistry major at Georgia Tech and graduation from North Carolina. Evans bought a Lotus Europa (“just as ragged as you could get”) in college went through several Corvettes. Still, the idea of building cars persisted, first V-8 conversions of Corvairs and then a homebrew Cheetah-like sports car. But by this time, DOT regulations – which Evans regularly ordered and threw away in disgust – were too restrictive permit anything so crude. He started building a transverse mid-engine V-8-powered car but quit when the cost of designing and developing an original body and transaxle were too much.

It was time to get practical. Before the transverse-engine car project, a friend had asked Evans to do a study on converting an IMSA GTP car for the street. The cost, realistically $150,000, was too much. But it started Evans thinking. Why not, rather than start with a whole car, start with GTP parts, and simply add what you need to make a car? After a thorough search of cost and availability, Evans bought Downing’s used (and damaged) Argo JM19 center section. That centersection was to become the prototype Evans Series 1.

From the outset John Evans planned to build cars to sell, not just a single-issue play toy for himself. Suspension with 5 in. of ground clearance, double A-arms up front and five link independent in the rear, both with concentric coil springs and shocks, was drawn and manufactured. An L98 Corvette engine, stock in deference to emissions considerations, was installed in the engine bay, mated to a ZF 5D5-25 five-speed limited-slip transaxle.

The nose and tail of Kevlar with vinyl resin was outlined, each piece with the strength and flex to meet federal bumper rules as a whole. A DOT-spec windshield was ordered – at a mold cost of $6000 – and installed along with a modified Mazda wiper with Lotus Esprit wiper blade. Because off-the-rack Recaros and such were too wide and racing buckets don’t have DOT-legal headrests, original seats were designed, the driver’s with Porsche derived fore-and-aft and tilt and adjustment. A GM collapsible steering column was used and the dashboard laid out with DOT requirements in mind. A heater/defroster and air conditioner were devised. And, of course, a passive seatbelt arrangement was designed, was shoulder belts that go up with the door.

Details from the proper headlights to the center high mounted stoplight added hours of effort to the straightforward work of making an automobile that worked. Of course, that was just the DOT safety requirements. Because he was using a stock Chevy engine, Evans thought the EPA’s emission requirements would be easy. Wrong. He was about to enter a Never Never Land of coast-down tests and catalytic converter tests and mileage tests and evaporative emissions tests. Because he used only parts which have been proven and original manufacturers test, he had he only had a 5000-mile test instead of the full 50,000-mile durability test. Many tests and dollars later (John Evans credits engine man Chuck Jenks and GM engineers for going beyond the call of duty), the Evans Series 1 is now emissions legal, complete with all the required labels and EPA rating of 26 miles per gallon highway, 19 city and 21 combined.

DOT requirements, however, are “self certification,” which means you do your own testing and then if the government later disagrees with you, your product is subject to recall. That’s sort of like getting a job and then having to return your pay if someone later decides you didn’t do well enough in freshman algebra.

Be that as it may, John Evans has his prototype on the road and, as you might expect, it causes as much excitement as a UFO landing in the National Enquirer’s front yard. On the freeway it’s followed by the curious like a mama duck by her ducklings. Park it, and is equal-opportunity question generator. No one can pass by without asking what it is, how much it costs and, of course, “What’ll it do?” Evans says he’s even had people climb in uninvited when he has stopped for gas.

That’s amazing, if only because entry is not that easy. The doors flip forward, Countach-style, the door handle inside the scoop in the door. The next step is, well, to step on the side pontoon and thence onto the seat and then wriggled down in as best you can. Once in, there is a surprising amount of room for anyone other than a first-round draft pick for the NBA. Headroom, shoulder room, even foot room is more than adequate, though hip room, particularly for the passenger (the cockpit is asymmetrical in favor of the driver) is a snug fit. There’s no trunk and no glovebox, just room for a bag of Doritos and a 6-pack of warm soda behind the seat, and if your passenger complains about the duffel bag in the footwell, well, you need a different passenger.

With recumbent seating, closing the door gives the feeling of a sarcophagus with a view, and a difficult view, at that. The windowsill is at chin level, as is the top of the dashboard, and the driver simply cannot see objects that are low and close by (there isn’t much need for that on the racetrack). Even the front fenders are out of view. High curbs and head-in parking require care and because the drivers sits nearly in the center of the car, Lane placement must be mentally recalibrated as well. In traffic, you’ll feel like a first grader at an adult party. Everyone is taller and your only view is through everyone’s legs. Despite the lack of a rear window, rear vision is quite reasonable, the high mounted driver’s side mirror giving a panoramic view over the back of the car, the right side mirror filling in what’s missed.

The 350-Q-in Corvette engine in a 2290 pound (wet) automobile means you don’t have to pay too much attention to what’s behind you anyway, except for those cars with funny paint jobs and lights on the roof. Evans automobiles claims zero-60 mph in 4.9 seconds, the quarter in 12.9 seconds at 111 mph and top speed just shy of 180 mile-per-hour with a 3.55:1 ring and pinion.

If it’s a race car for the street you want, the Evans Series 1 will not disappoint. Even with a converter and muffler behind each header, engine noise is ever present, particularly at speed and during acceleration. Evans doesn’t use noise insulation and doesn’t install a radio. Interior appointments are Spartan, and a leather-covered pad on the door only serves to accentuate its purposeful austerity. The rollbar is padded in the gearshift mechanism covered, but otherwise it’s bare. If you want to fancier interior, get an F40.

Steering effort is moderate. There’s no power assist but there’s only minimal weight over the front end. The clutch, well, hope you don’t get caught in traffic, although with torque abundant at any speed there’s little need to shift. I had no chance to begin to experiment with the ultimate cornering capability. Suffice it to say, it’s up there where the guys with the cherry-tops and light bars will want to talk with you if you try. The prototype wasn’t fully adjusted for bump steer, though irregular road surfaces had little effect and the ride was acceptable. Monster speed bumps evoke a “will this thing clear?” response, however.

The production car will be built around an aluminum honeycomb tub, gusseted for rollbar in front and rear subframe pickup points. The rear subframe will be a tube frame, while the front will be a tube frame reinforced with honeycomb for crash strength. The center section body, only there to push the air out of the way, is not structural and isn’t bonded to the tub. In the production cars it will be polyurethane foam sandwiched between fiberglass and graphite cloth.

The front fenders will have headlight buckets with small rectangular 2E1 headlamps and turn signals under plexiglass covers. Front side marker lights will be added and the rear side lights changed. The windows, which can now be removed by a number of small thumbscrews, may receive sliding panels and larger thumbscrews. Think of it as a world’s widest T-top. John Evans calls air-conditioning a $1500 option, but with all that glass overhead, I’d call it a necessity.

The external shape of the Evans cannot be changed, at least without the approval of the EPA; thus the vents, scoops and louvers will stay as they are. The engine is another unchangeable item, at least for the time being. A 430-cu-in., 420-BHP engine is “due in 1991.” That engine, however, with have to undergo the EPA’s 50,000-mile durability test and that expensive proposition awaits the launch of the L 98-powered Series 1. Evans notes that retrofit would be possible when the 430 is certified.

Evans is also restricted in tire choice. The EPA doesn’t allow a change to tires with more rolling resistance. That means the BFGoodrich 205/50R-15 up front and the 265/50R-15 rear tires (on 7.5-and 10-in rims, respectively) are baseline, as they were used for the EPA coast-down test. The rears can be changed, since aerodynamics won’t be affected, and Evans plans to use some 315/35R-17s in back which have less rolling resistance in the baseline tires.

Of course, all this EPA/DOT stuff is boring, is it a credit to John Evans that he’s persevered. There is a delightful absence of hype and genuine modesty about Evans readily admits to help he received from composite specialist Blanton Redford, fabricator and computer expert Steve Cooper, and engineer Rick Presley, as well as his sister for typing all those government forms and his wife, Amy, for, well, putting up with a dreamer.

Production will be limited to about 10 cars per year. When we last spoke, Evan still had no US takers for this $85,000 American supercar. Ironically, interest from Belgium may lead to Evans Automobiles’ first sales.

The Evans Series 1 is a sports car in the purest sense of the term. If there’s any justice, if there’s any sense in the supercar market, it will be a success. And someday, maybe, Scottdale will be as well-known as the city where those other high-performance cars are built.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.