History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek December 29, 1986

It shouldn’t have existed, the Daytona Spyder. At least it shouldn’t have been what it was. By tradition, Ferrari had usually differentiated between coupe and spyder versions of his cars. Spyders weren’t just topless versions of roofed models. They were completely different cars, sharing engine and chassis, perhaps, but with wholly different bodies.

(Even the names of the cars evolve from the internals. For example, the Daytona Spyder was officially the 365 GTS/4, four 365cc per cylinder Grand Touring Spyder with four cams.)

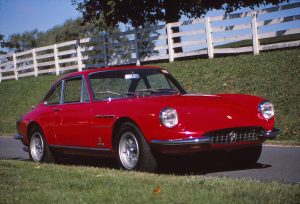

The Daytona Spyder changed all this. It was simply a convertible version of Pininfarina’s brutally styled grand touring 365 GTB/4 which had first appeared at the 1968 Paris Salon. It went into production in 1969. Scaglietti, the vaunted Italian coachworks firm, built the bodies. The open version followed, debuting at the Frankfurt Auto Show late in 1969 on the stand of Auto Becker, the German importer for Ferrari.

It, too, was designed by Pininfarina, sharing the coupe’s knife-edge prow and elegantly simple sides. But instead of the bold greenhouse of the closed car that made the Daytona look in profile like a cocked and loaded slingshot, the Spyder had a broad rear deck. It was a massive alteration, more than usual for a convertible version. The coupe was a true fastback with no hint of deck or even rear fender crest, the sides sweeping upwards from wheel arch to roof without interruption. That had to be changed completely for the Spyder. It shouldn’t have worked but it did, and masterfully: while the closed Daytona resembled an artillery shell, the Spyder was an arrow, light and sleek.

The Frankfurt Show convertible generated sufficient interest to spur production. Chuck Queener, writing in Motor Trend in 1971, gave another reason for the Spyder: Scaglietti was building more Daytona bodies than Ferrari could make chassis for. To slow Scaglietti as well as satisfy those who wanted an open Daytona, it was decided that every fourth coupe should be cut down. If that’s true that the Spyder was to slow Scaglietti’s production, the proposed ratio was never met. Of approximately 1,400 Daytonas made, only about 127 were Spyders. More than that number of coupes have since been converted.

Ferrari Market Newsletter publisher Gerald Roush doubts the “slowdown” theory. He suspects the Spyder was a result of inquiries after the Frankfurt show. He believes that after having agreed to do one and then another special convertible, the factory decided to produce a production Spyder, making changes to frame, floor pan and so forth. Probably not more than a dozen initial “factory cut” cars were made, but Roush repeats that there is no way to be sure, as Ferrari is not forthcoming on such matters.

Demand for Spyders wasn’t enormous during the years the Daytona was produced. Serious drivers preferred the closed car. Legend has it that the engineers at Modena opposed the Spyder concept because it would have been impossible to drive the car with top up or down at 150 mph or higher, speeds at which the Daytona was intended to cruise. (Road & Track verified the top speed of the coupe at 174 mph.) Of the original 127 Spyders, at least 96 came to the US, where such speeds are mostly academic, perhaps giving substance to the “engineer” theory.

At least the first of the Daytona Spyders were actually cut from completed coupe bodies (not finished cars), making them conversions before they ever left the factory. Spyders varied from the coupes in having steel inner fenders and slightly heavier frame tubes for enhanced rigidity. Not that the tube frame of the coupe was weak: The steel skin – hand fabricated in small pieces by Scaglietti craftsmen and fitted carefully together – was completely unstressed as a frame member. As a result, Spyders were relatively free of rattles and cowl shake.

One area in which the Daytona Spyder did not shine was its top. It was difficult to raise and lower, with pieces having to be guided into place rather than falling naturally and care had to be taken not to pinch the fabric. The seats had to be moved forward in their tracks and even then the top frame just missed the seatbacks as it was folded. The rear window was that same plastic that oxidized so quickly on Fiat 850’s. All in all, the top, which was the car’s purpose for being, was in functional terms its greatest weakness.

Aesthetics were another story. Unlike many roadsters, the Spyder looked handsome with its top up, the steeply raked windshield meeting the blunt, curved shape of the fabric in an attractive contrast while not upsetting the vehicle’s overall proportions.

The Ferrari Daytona Spyder was an example of rare synergism, balance and control. It was also that rare example of a moment when perhaps it was best that the advice of Ferrari engineers was not followed. The Spyder, like a student of Philosophy 101, did not need to prove the reason for its existence. It is simply demonstrated the good judgment of those who saw that it did.

The Daytona Spyder’s scarcity compared to the coupe inspired enthusiasts of al fresco exotics to cut the fastback off the coupe, actually increasing the value of a decapitated coupe. I wrote about that in another article that will be republished on Remember Road. Subscribe so you don’t miss it when I do.

Current value of the Daytona Spyder, per classic.com, is two and a half million plus, while the coupe is a mere half million, plus or minus depending on condition and provenance and such.

Need more on Ferrari cabrios and spyders? Click for the Mondial t Cabrio, the Dino 246 GTS, or 250GT Spyder California.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.