History originally published in AutoWeek January 30, 1984

Let’s talk desire. Let’s talk lust. Let’s talk Testa Rossa. Ferrari Testa Rossa, of course, for no other maker has been so brazen as to borrow the name, as did Pontiac with the GTO. But more specifically, let’s talk 250TR, the V-12, not the four-cylinder which preceded it. While we’re at it let’s narrow it down to the ‘58 TR belonging to Dick Merritt, Bethesda Maryland, author and historian of the Ferrari Club.

Merritt’s 250, like most of the Testa Rossas, was a “customer car,” because even though it was designed for racing, even though there was a factory team to race the sports cars, the 250TR was primarily built for sale. Some would be raced, some would live only on the public road, and some, like Merritt’s, would find their way into the hands of gentlemen racers such as Peter Monteverdi. Yes, that Monteverdi, later to become best known for his Chrysler V-8 powered sports cars. Monteverdi, the original owner, used the car for hillclimbs and similar sport, and sold it to some French enthusiasts who invaded its hindquarters to install an independent rear suspension system of their own design. After racing it to no significant success, they sold it to a collector in France, who set the racer back to the original. And it was on to Merritt.

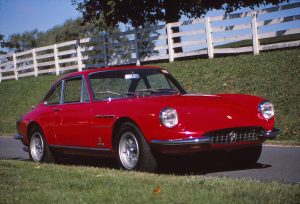

To the cognoscenti, Merritt’s TR is obviously a ‘58. That was the only year for the distinctive “pontoon fender” style, discounting the prototype run at LeMans in 1957. Even in 1958, some of the factory team cars had conventional round noses and smooth sides.

The pontoon fender concept was actually intended to be a means of cooling the massive drum brakes. Ferrari had yet to adopt disc brakes, countering with drums that filled the 16-inch wire wheels. The pontoon fenders were actually what was left after a drastic cutting away of bodywork from the nose and behind the front wheel. Thus exposed to the airstream, or so the theory went, enough heat could be dissipated to keep the drum brakes effective. As an added plus, a vent to the engine compartment was cut to allow the escape of hot under-hood air.

Keeping the brakes cool it may have done, but no more than scoops in conventional fenders. And despite the wind-cheating look, the shape produced turbulence. And therefore drag. In aerodynamics, what you see is not always what you get. For 1959, the “Grand Prix car with fenders” body from Scaglietti yielded to more conventional forms from Fantuzzi. And anyway, with Dunlop discs replacing the outmoded drums in 1959, the need for brake cooling was not nearly so critical.

The chassis itself was tubular and suspension was by A-arms and coil springs in front. In the rear, coils with either a live axle or a De Dion unit were used. In 1960, Ferrari added independent suspension to some of the cars, and although the 250TR yielded to the mid-engined 246SP in 1961, it was still Testa Rossa which more often than not won the laurel wreath. And in 1962, the privately entered 250TR of Bonnier and Bianchi managed a first overall at Sebring.

But regardless of the suspension or the bodywork, the real heart of the car is the part that gave the car its name: the engine. Testa Rossa. Red Head. Strictly speaking, this is crimson paint on the valve covers, but it’s really more of a warning.

The engine was a development of the SOHC 250 GT unit, sharing its 2953 cc displacement from an oversquare 73×58.8 mm bore and stroke. But whereas the GT produced 200bhpat 7000 RPM, the TR went to 7200rpm for an additional 80 horses, thanks to modifications including machined connecting rods, a compression boost from 8.5 to 9.8:1 and a new combustion chamber design; and a magnificent column of six dual-throat 38DCN Weber carburetors, fitting the 60-degree V-12 as if they grew in place, sprouting velocity stacks into the purely functional blister.

Twin coils mounted through the firewall are paired with dual six lead distributors aft of each cylinder bank. The half dozen exhaust manifold tubes per side lead into a common collector which, after exiting to the rear of the front wheel, separates into two muffler shaped objects which do little to reduce the sounds from the four megaphones under the rounded tail.

Ah, the sound. So much has been written about the song of the V-12 Ferrari that little is left to tell that isn’t a cliché. On the other hand, it cannot pass without mention. There’s actually something of a Jekyll and Hyde affect. At idle and below 3500 RPM, there’s a rolling rumble that tumbles out of the pipes, a kind of latent threat like that embodied by a squadron of B-29s. Hit the magic number, though, and the beast lays back its ears, the noise gets organized into an internal combustion scream that won’t quit ‘til redline. No crystal within several hundred yards is safe. That change in timbre is the clearest, most unadulterated definition ever of “coming on the cam.”

All this is controlled from a cockpit that is as sparse as in any racer anywhere. The doors have no interior panels nor exterior handle. The latch itself is embarrassingly crude. The passenger’s feet share the foot well with the battery and the electronics are in open view under the dash.

There is no trunk. The smoothly molded tail with its button taillights and driver’s head fairing contains a mammoth fuel tank with little room to spare.

There is no speedometer. The big steering wheel frames a similarly large chronometric tachometer, with lesser gauges placed more for function that aesthetics. The clutch is heavy and the transmission a bear, but this is where it all happened.

Enzo Ferrari foresaw the three-liter limit that the CSI would impose beginning in 1958 for the Manufacturer’s World Championship, and with the 250TR he was ready, unlike many of his competitors who were left scrambling to catch up and never really did. During the next four years, from 1958 through 1961, the Testa Rossa in its various forms would dominate sports car racing. Drivers read like an honor roll of the era: Hill, Gendebien, Gurney, Daigh, Behra, Ginther, Von Trips, Rodriguez, Frere, Hawthorne. And the race courses, like venues of history: Buenos Aires, Sebring, Targa Florio, Nurburgring, LeMans.

Especially LeMans. Gendebien won there in a TR three times, with Hill in 1959 and 1961, and with Frere in 1960. Consider the Testa Rossa at the Sarthe circuit, headlights tracing an all too inadequate stretch of the Mulsanne, a dash lit to show a tach reaching for maximum RPM. The cool dampness of the night air mixes with the heat off the engine, the V 12 holding steady high pitch. There’s no Doppler effect in the cockpit.

Just an intense awareness.

Ahead rides a visage locked in glassy-eyed stare, as lean and hungry as Cassius on the Ides of March, amoral as a shark. Anything that tactile, that sensate, has to spell desire, has to spell lust, has to spell Testa Rossa.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.