History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek August 11, 1986

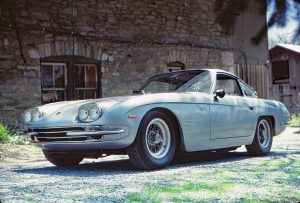

I was told to look for the Urraco. The airport at Savannah, Ga., is small and, sure enough, Don White’s little Lamborghini, a ‘74 P250, was the only one at the curb. Don was standing nearby, and, after introducing ourselves and loading my gear into the small but usable trunk, we were off.

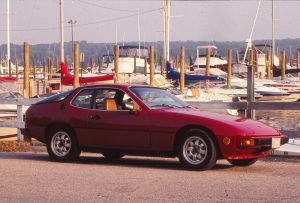

The Lamborghini Urraco P250 was first displayed at the 1970 Turin Motor Show and received immediate worldwide attention, for here was Lamborghini, previously having produced only expensive V12 tourers and sports cars, preparing to build a lower-priced car with a mid-engine V8 and a 2+2 to boot. More exotic than a Porsche and cheaper than a Dino 246, it just couldn’t miss.

Except that it would be two years until production and the model wouldn’t arrive in the US until 1975, hardly an auspicious time to launch an exotic. The oil crisis was in full swing, the newspapers full of gloom and OPEC at full strength. In fact the OPECers were about the only market left for exotics, and they were more interested in the Countach. Add increasing government meddling (and not just in the US – France, for example, would disallow the louvers over the engine) and the environment was hostile, indeed.

We hammer south on I-95 towards an appointment in Orlando. The steering wheel and pedals are offset to the right to clear the front wheel well, and initial annoyance only. The dash, however, looks too homemade for a car that sold for $25,000 new. The layout, with a tach to the left of the steering wheel and the speedo to the right and all the little gauges in between will either greatly please or irritate.

The little blue bullet gets attention. We can’t pass a car without heads spinning. A side trip onto the sands of Daytona Beach could be called Trolling for Bikinis. Wanna get noticed? Take an Italian exotic onto Daytona’s drive-on beach.

The shape was drawn by Bertone’s chief styling engineer, Marcello Gandini. Designed for relatively mass production – plans were for 1000 a year – the car had a unit body built by Bertone. The 2+2 layout was a bid for more utility, but the back seats could fairly be called false advertising. Small children would be cramped.

Even on the beach the engine never misbehaved, never overheated. The occupants, however, melted. White’s car is a 1974 European model, a P250 S, the last letter signifying upgraded accoutrements, such as power windows, but no more power. And for this car, no air conditioning. Surprisingly, it’s not hotter than any other car without air would be, despite its engine location. The exotic timbre of the exhaust combines with a responsiveness that gives a satisfying feel

The V-8 is nestled transversely between the rear wheels, offset to the right with the Lamborghini designed and built five-speed to the left. The single overhead camshafts are driven by toothed belt, then a fairly new concept. Four downdraft twin-throat Webers grace the top of the engine, visible through the rear window from the passenger compartment. The little engine – 2463cc – is extremely oversquare, 86 x 53mm, and is redlined at 7500 RPM. Power depends on which version. European model got 182bhp (DIN) while the America-only P111 was rated at 175.

The Urraco was criticized for a lack of power, but New Zealand-born factory man Bob Wallace takes exception, having stated instead that the car was overweight. The distinction isn’t as absurd as it might it first seen: the P111’s listed torque was 139b-ft at 5750 RPM, the P250 had lb-ft at 3800 RPM. And that’s to pull around a 3000lb curb weight. In contemporary testing the P111 turned the quarter in 17.9sec, 0-60 in 10.1 second and a top speed of just under 125 mph, exactly what would be expected from an aerodynamic, high-rpm power/low torque package.

Florida is a lousy place to test drive a sports car. Like most basically flat areas, the roads are straight – why curve them? – and, while that’s fine for acceleration runs, it’s hard to get a feel for the cornering prowess. Thank goodness for the cloverleaf, the DOT’s answer to the skidpad. The Chevette-clear runs we managed proved the Urraco to have vice free handling, neatly balanced with plenty of stick. Just like the book says, power on and the nose runs wide, power off and it tucks back in. “Understeer” and “oversteer” seems much too harsh to use.

The Urraco’s suspension is from Lotus by way of Fiat, using modified Fiat 130 struts front and rear. Standard wheels were Campagnolo 14×7.5; tires were Michelin XWX205/70VR-14. Weight distribution is 43/57%, front to rear. Lateral acceleration was tested at .791g. The Eagles on White’s car would surely prove faster.

Back on the plane at Orlando international I had plenty of time to consider the fate of the Urrao: it was, for Lamborghini, a failure. Production, including 2.0 and 3.0 liter variants, totaled 776. The financial burden almost finished the firm.

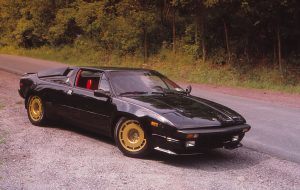

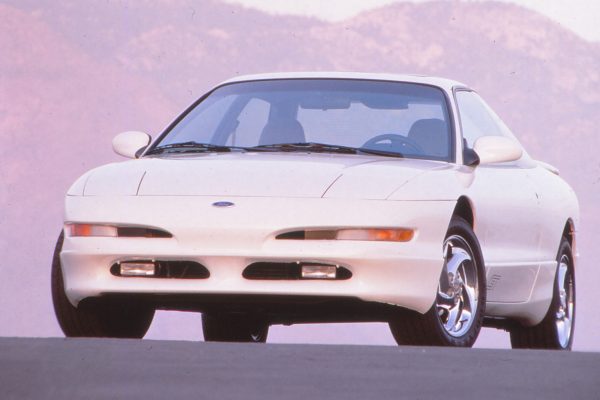

But the Urraco, last built in 1977, lives reborn in the Lamborghini Jalpa. The Dino 246 and the Maserati Merak, the Urraco’s contemporaries, are long since gone. And the Urraco, for anyone with soul enough to appreciate an attractive shape, impeccable handling and a dim tympanum tickling exhaust note, can be nothing but a success.

An “affordable exotic,” is that an oxymoron? The car wasn’t inexpensive when new. The U.S. price in 1975 was $22,500. That sounds enconocar cheap in today’s prices (2023), but adjusted for inflation, that’s approximately $120,00. Today, according to classic.com, the various versions of the Urraco have sold for an average of $82,406, so anyone who locked away a Urraco as an investment took a mighty hit.

On the other hand, anyone who used a Urraco as a daily driver didn’t fare much better as the Urraco earned a reputation of unreliability.

Time flies. When this article was first published, the Lamborghini was little more than ten years old. Now it’s almost 50.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.