History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek March 31, 1986

Tears are streaming back into my ears. The 1100cc Coventry Climax engine is bellowing angrily as I try to maintain a steady speed, a futile effort anyway but more difficult by the fact that the Lotus’ non-adjustable pedals have forced me to slump low, while its narrow footwells have required the whole operation be performed in stocking feet. It’s no use; the car is leaping about the road steering seemingly of its own volition

The tears come from, first, terror, secondarily the fact that the hard tonneau of this 1956 Lotus 11 LeMans, which includes the windscreen, has been removed so that Jeffrey Griffith, co-owner with Ron Snow, can ride shotgun. I steal a glance a Griffith to see if he, too, realizes our great peril. He’s grinning. I’m about to hurt ourselves badly, absolutely destroy his beautiful little car, and he’s grinning.

I have, to a certain extent, been set up. Griffith knows perhaps as well as anyone that the combination of a bumpy road and a ‘56 Lotus 11 would terrify a driver new to the car. It’s the fault of the split-axle front suspension, actually an English Ford front axle cut in half and pinned. It’s probably the most rudimentary form of independent front suspension and it has one very nasty habit: suspension travel causes substantial changes in camber, and camber changes in this type of suspension will impart a steering thrust in the direction of the lean. Hence as the 11 travels over bumps, it steers itself. Not to worry.

For Lotus the split front axle dates back to the 1948 Lotus Mark I, Lotus founder Colin Chapman’s college days Austin 7, modified for trials. Even as Chapman, now deceased, drifted from trials to pavement competition, the split axle, so useful for gripping a muddy hillside, was retained. Despite what would seem to be obvious disadvantages, Chapman believed it would provide better road holding with less speed loss through corners.

The theory went like this: Chapman had observed the effect of body roll on various suspension types. Generally, as a car leaned in a curve, the outside front wheel went to extreme positive camber angles. To counteract the camber thrust, the driver had to feed in more steering lock. While this got the car around the corner, the large slip angles scrubbed off speed not easily replaced in cars with small displacement engines.

One solution too often used was to firm up things enough to prevent roll. But Chapman was a believer in a rigid chassis and soft springs as the key to road holding. Thus the rationale for the split axle, which would maintain almost correct camber as a car leaned in a turn. Since the cars were intended for the predictable world of smooth racetracks and manicured English country lanes, the random hoppings we encountered on uneven pavement were not a great concern.

The fact is that it worked. Lotus won the 750-1100cc class at Le Mans in 1956, taking forth in the Index of Performance and a stunning seventh overall. Still, for 1957 it was eliminated for the Le Mans version of the 11 in favor of the Lotus Formula 2 car’s front suspension (buyers of the Club and Sport versions, however, got still got the split axle.

Of course the Lotus 11 is more than a front suspension. It’s a Frank Coston designed aerodynamic body over a Chapman space frame, available in top-of-the-line Le Mans version (with de Dion rear suspension, four-wheel Girling disc brakes – diff mounted at the rear – and choice of Coventry Climax engine), Club (with a live rear axle, drums all around, and the Coventry Climax), and Sports (with a tamer Ford 100E engine). Ironically, the wraparound windshield with metal tonneau that came with the LeMans version was illegal at LeMans, which required a full windscreen.

The 1100cc SOHC Coventry Climax engine, canted about 10 degrees to the left for a lower hood profile, originally came with two 1.5-inch SU side-draft carbs, but like most self-respecting Climax race motors, the one in the Griffith/Snow car was later equipped with 40 DCOE Webers. It also has a five bearing cam, good for a reliable 7500 RPM. Altogether it results in just about 100 BHP, or 1.5 BHP per cubic inch. Not bad for what started out as a portable fire-fighting pump engine.

The doors are piano-hinged along the bottom, Chapman’s ruse to beat the rule that the cars had to have doors at all. Actually, it’s easier to ignore the doors. Opening them only makes the step into the seat longer. And once in, is no Paradise in Velour. Riveted aluminum and tubing are the rule, except for the exposed driveshaft U-joint and naked transmission.

Despite the sports car competition class pretensions, it’s really a lousy road car. Steering has limited lock; the faired narrow fenders have a price. Weather sealing, without installation (want to drill holes??) of the top and full-with windscreen, is obviously non-existent, as are heater, defroster and multi-function stereo radio/tape-player/biorhythm computer. The radical engine is noisy and peaky. And there’s that dreadful swing-arm bump steer.

Later Griffith told me that they checked afterwards to find 0.5 inch too much toe in, which would account for some of the dartiness we encountered. And anyway, said Griffith by way of consolation, “you weren’t out of control. You only thought you were.”

Sure, but next time let’s find a smoother road. Like Mulsanne.

Maryland requires a front license plate. There was none on this car, and the car certainly wouldn’t have withstood even casual inspection by any authorized officer of the court. I had wondered about the legal responsibility—driver or owner—though not enough to keep me out of the driver’s seat.

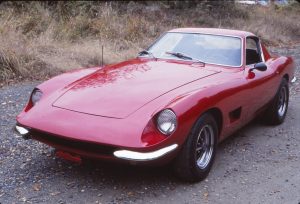

Compare the Lotus 11 to the Lotus 23, of just some six years later.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.