History/driving impressions originally published in European Car August 1995; republished by the author

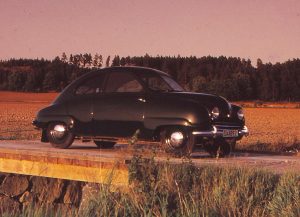

The first Saab to come to America, at least officially, was a 93. It was an unusual addition to the automotive landscape. To a continent rife with aircraft-inspired automobiles came a truly aerodynamic automobile, and one made by an aircraft manufacturer, no less. Yet most Americans thought it was the Saab that looked peculiar, not the tail-finned behemoths of the American road.

Nevertheless, the Swedish teardrop found an audience in the U. S. Pilots appreciated it, and it appealed to engineers, though doctors were the single largest group of buyers by occupation. An autumn 1958 survey by the University of Connecticut also found Saab owners to be the most politically liberal, second only to those who listed walking as their primary mode of transportation. Cynics might add that non-mechanically inclined owners of early Saabs tended to become walkers. The survey, though, also found 94% of Saab owners said they were “satisfied” and only 1% “dissatisfied.”

The 93 was a big improvement over the 92, however. The 92, with a two-cylinder two stroke was, for all its sophisticated styling, marginal transportation. Profoundly underpowered, it had a top speed – flat out – of about 60 mph. Add hills, passengers or headwinds or, egad, a combination thereof, the speed dropped dramatically. It was adequate for Europe, where most people had never been able to afford a car at all. Its competition was the bicycle, the motorcycle and the hordes of bubble -shaped micro cars that briefly flourished on the Continent. But in the United States it would have been a commercial disaster. Most 92s stayed in Sweden. (Read more about the Saab 92 here).

The Saab 93 was something else. Like the 92, its name was simply a sequential model number with no particular significance. But under its restyled hood was a three-cylinder engine. The displacement wasn’t increased – the 92’s twin displaced 764 cc, the 93’s triple, 748 cc. But the last of the 92s made 28 bhp, the new 93 made five more horses, an 18% increase, and was also much smoother.

It also fit neatly inside the 750cc class for competition. The 92 had to compete in the 1100cc class, where stiff competition came from the smaller Porsches. The 93 would race mostly against small engined cars from France and Italy.

The three-cylinder engine was mounted longitudinally instead of transversely, the crosswise twin one of the 92’s inheritances from DKW, whose pre-war powertrain Saab engineers had studied in devising the 92. The longitudinal mounting of the engine, however, required a completely new and very compact transmission. It was still a three-speed and column-shifted, but the freewheeling was retained, although it could be disengaged from the driver’s seat. Freewheeling was necessary to keeping the engine from starving for oil when the carburetor was closed and the engine turning at speed, such as when coasting downhill.

The radiator was actually above and behind the engine (as on the 92), cooled by a fan mounted on the shaft atop the engine that was turned by a pulley and vee-belt off the crankshaft pulley. A radiator blind was installed behind the grill.

The new triple had an assembled crankshaft, using six identical webs with press-fit crank journals and crank throws. In the mains were four single-row ball bearings. Because the two-stroke was crank charged, the three crank chambers had to be sealed from each other, and ordinary piston rings and closely tolerance grooves provided the sealing. Big end bearings were double-row roller bearings.

The carburetor was a single-throat Solex 40A1. Two silencers, one across the front of the car, quieted the exhaust. The electrical system was 12 volt, the distributor a conventional automotive type. It had to turn at crank speed, however, to spark the two-stroke every time the piston came up.

Although the engine was the 93’s most significant advance, the suspension was revised as well. Front and rear track was increased, and the 92’s torsion bars, which tended to rattle as its bushings wore, were replaced by coil springs. Front suspension was by double A-arms, with the spring on the top arms, an anti-rollbar on the lower arms. The independent trailing arm suspension on the 92 was replaced by a U-shaped dead axle on the 93. Linkage and shock absorbers were arranged to eliminate the oversteer caused by the 92’s set up.

Behind the firewall, the body was largely unchanged. The split windshield and the rear-hinged “suicide” doors continued, although from behind the observant would notice new taillights. Changes to the front, however, left no doubt that this was a new model, the “Italian-inspired” grille getting the distinctive identification.

The Saab 93 went into production on December 1, 1955, although American imports didn’t begin until 1956. That first year, only 295 were sold in the U. S. These cars had sealed beam headlamps, flashing indicators (instead of semaphore), a rubber mat in the luggage compartment, heavier bumpers, whitewall tires, chrome rims around the windows and push button door locks. U.S. sales rose to 1691 for 1957, 3672 in 1958 and 6176 in 1959.

Part of the success was due to continuing improvements to the 93, with a sufficient number 1958 to warrant the designation “93B.” These were mostly detail, including a crudely adjustable front seat and standard seatbelt mounting points, but a 93B is easily identified by its single piece windshield with parallel wipers. The 1959 model received larger 9.0-in. (Instead of 8.0-in.) brake drums, windshield washers, better seats and padded visors, among other changes. A spring of 1959 addition was a sunroof model, the 93F – for “front-hinged doors) – appearing in the fall of 1959 as a 1960 model, as the new 96 model had been delayed. (The 95, a wagon version of the 96, debuted in 1959).

A Saab 93B sunroof model is a daily driver for owner Matt Sheidt of Dayton, Ohio. Matt, who is younger than his car, even uses it for highway trips, recently driving to Vermont – and back. It’s also an ongoing restoration project, with the exterior mostly complete and the engine mechanically though not cosmetically restored.

It’s a kind of perverse pleasure to drive. Acceleration is anything but stunning, about what you expect from 38bhp SAE, but there’s a peculiar smoothness from the triple, probably attributable to the power coming on every downstroke. It does feel like a very little six-cylinder four-stroke engine. There’s a lot of linkage to shift with the column-mounted lever, but the next gear will come provided you don’t hamfist it.

Driving the car, in fact, is a study in subtly and planning. Watch the rpm, watch the gears, and the Saab motors easily. Just don’t expect too much off the bottom. And watch those hills. A good running start and keep the revs up and you will make it.

Of course there’s that pop-pop-pop exhaust as the car free wheels and the engine “four-strokes.’ Saab was the only carmaker to make any serious headway with two-stroke engines in the U. S., And the Saab 93, with its little popcorn popper, was how it all began.

Saab comes to America

The Swedish Parliament, viewing the darkening political situation in Europe, passed a resolution to strengthen national defense, including the formation of the Royal Swedish Air Force, as well as encouraging the establishment of a modern aircraft industry in Sweden as soon as possible. With that encouragement, a group of investors founded Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget (Swedish Airplane Incorporated). Thus began Saab, maker of military aircraft. It’s a role that the company, now Saab-Scania, still fills, along with making civilian aircraft, including a twin turboprop model used by airlines in the U. S. and elsewhere.

But in 1945, military and civilian aircraft production did not appear to be sufficient for the young company’s survival. Saab management, however, saw an opening in the automobile market with a substitute for the DKW. The German front-wheel-drive two-stroke twin had been popular in Sweden before the war. Production of the Saab 92 began in December 1949.

A year before that, a young American by the name of Ralph Millet went to work for Saab in its Manhattan purchasing office, hired to buy parts for aircraft production. “But shortly thereafter they asked me to go over to Sweden and help them buy machinery for this new plant they were setting up to build automobiles,” recalls Millet.

A stay of about three months in Trollhattan was followed by a trip around the United States buying surplus machine tools. “We also bought a couple of big new Clearing presses, which I thought were tremendously big. I saw about five or six years ago there still operating. But, they’re tiny next to the modern presses.”

Anyway, in 1952 Saab closed the office in which Millet had worked, and Millet turned down an offer to represent Saab at $500 per month to join with a friend to form Independent Aeronautical, an exporter of aircraft equipment. He still did some buying for Saab, however, and in 1955 Millet received a letter from Tryggve Holm, president of Saab, who planned to visit the United States to shop for an automatic pilot for Saab aircraft. Would Ralph please make the arrangements with Bendix, Honeywell, Sperry and so on? Millet agreed.

Millet remembers Holm as “a very tall, domineering, formal person. When he walked into a room he was one of the people that you knew that someone was there that was important. I used to get scared to death every time I saw him,” Millet now says, smiling.

The pair was in Minneapolis visiting Honeywell when Holm, seeing Volkswagens on the road, said to Millet, “if they get that Volkswagen over here – that car – we ought to be able to sell the Saab 93. We got a new car now, Ralph. It’s a great car. It’s got a three-cylinder engine.” Millet’s voice added the emphasis, making it clear that Holm was quite proud of the great advance. The 92, after all, had only two cylinders. Holm obviously had overlooked the sixes and V8’s in America.

Despite his awe for Holm, Millet deemed it necessary to dash the Swede’s misguided enthusiasm. “I said, ‘Tryggve, you’re never going to sell a two-cycle car in the United States. That’s ridiculous. (Owners) have to mix their own gas.’” Unlike Sweden, the U.S. didn’t have mixing pumps for oil and gas, something Holm did not know.

“And he said, ‘Oh well,’” Millet’s voice reflecting Holms mild disappointment.

Millet didn’t hear anything more about it for the rest of Holm’s trip. “He was going to take a plane back to Sweden. I was going to drive him back to the airport. I went over to the Plaza Hotel where he always stayed and we had lunch together, and at lunch he said, “Find out when the next automobile show is in New York. I’m going to send you some cars and we’re going to put them in that show and we’ll see if we can sell these damn cars.”

That, says Millet, would be what would pass for market research for Saab.

Millet arranged for space at the New York auto show in the spring of 1956. Five or six cars were sent over, plus the first Sonnett.

At the show the cars attracted attention, but the surprise for Millet was Louis Strauss, an Erie, Pennsylvania, dealer who “sold MG and Triumph and practically everything in the book back in those days – except Volkswagen. He came up to me and said, ‘I want to buy three of these cars.’”

“I was absolutely flabbergasted,” Millet says, smiling. “I don’t think we even had a price at that time – how much we were going to sell them for. So I stalled him. And he came back the next day and said, ‘I want three of those cars.’”

Millet says they finally made a deal, Strauss somehow taking the cars back to Erie, but Millet was “aghast.” He was a buyer and seller of aircraft equipment. “I didn’t even know how to appoint a dealer, what kind of franchise to have or anything!”

And there was no company to sell Saabs in the U. S. “Just a little company, Independent Aeronautical,” says Millet. “And here we were suddenly in the automobile business.” A lawyer friend advised him to form a separate company, as car sales weren’t in (the) corporate franchise – or whatever it was.”

“I got in touch with the people in Sweden and said, ‘We should form a company over here to sell the cars. How do you want to do this?’ No answer. So I formed a company which was called Saab Motors, and all the shares in that company were owned by Ralph Millet.”

About three months later – typical for the Swedes who can never make a decision, says Millet—Saab finally decided they wanted the American company. “So I sold them all the stock,” says Millet, shaking his head in disbelief of his naïveté. “That was a big mistake. I shouldn’t have sold,” but then Millet reconsiders and remembering the lean years says, “maybe it was a good idea.”

So the company was formed. Millet was president but credits a sales strategy to a hire named Bruce McWilliams: “He said to me, ‘The first thing we ought to do is concentrate our sales in New England. You can’t sell it in the southern area. You’ve got to sell it in the winter climates.’”

The best way to get visibility, Millet thought, was to enter into competition. “We couldn’t afford advertising so we had to do something.” They decided to put the car in the Great American Mountain Rally, a 1400-mile event in New England in late November made even more difficult by unexpected snow and icy roads.

“They sent three cars from Sweden to be in that event, and lo and behold, we won,” says Millet, still surprised years later. “I remember the headline: ‘Saab wins GAMR.’” Out of 63 entries, a Saab 93 driven by Bob Wehman and Louis Braun finished first overall. Saab development engineer rally driver Rolf Mellde took sixth place, the other Saab coming in seventh overall.

And that, says Ralph Millet, was how Saab started in America.

The Two-Stroke Problem

Saab may have been launched, but it wasn’t all clear sailing. Millit’s concerns about two-stroke engines were well-founded. Although people bought them, “We had engines dropping dead all over the place. You cannot conceive of the engine seizures that we were having.”

One problem was oil viscosity. It wouldn’t mix well, particularly during winter months. The home offices suggestion of first pouring oil and gas into a small container and shaking it before adding it to the tank didn’t go down very well here. Instead, experienced two-stroke Saab drivers tell of tricks they used, such as keeping oil cans in the passenger compartment and then prewarming them between their knees before refueling, always carefully calculated at six to seven gallons so the oil would mix. And then, while the gas was added over the oil, the car was rocked by a foot on the back bumper.

A problem was that gas station attendants often disregarded the request to add a quart of oil with the gas, setting the proffered can aside to do the crazy car owner a favor. After all, you don’t add oil to an engine in the gas filler. But after refueling, the newly gassed Saab would go about two blocks before the premix in the carburetor was used up and the engine would sieze. As a result, owners usually trusted attendance only once.

Trollhattan ordered the U.S. office to ship seized engines to Sweden for rebuilding, but Millet thought that crazy. Instead, Millet established a rebuilding facility in the U.S., a decision that almost cost him his job about three times. Saab Motors didn’t exactly have a warranty but replaced engines for goodwill. Owners, however, didn’t always know that the engine had seized. Millet grins: “Someone would call and say the engine had failed, and we’d say “It’s the starter.” It wouldn’t turn the engine over.” Owners could take the news of starter failure better than engine failure, even if the engine were replaced free.

Millet says that, some 25 years later when he retired from Saab, Tryggve Holm sent a letter to Millet saying, “Ralph, if you had not given all those engines away, Saab wouldn’t be here today.” Says Millet, “It took that long to get any recognition for it.”

The two-stroke era ended in 1966-67 when Saab began putting the Ford V-4 engine in the Saab 96. Holm wanted to keep selling the two-stroke in the U.S., figuring, Millet says, that the news of the four-stroke being used in Europe wouldn’t cross the Atlantic. So to sell the two-stroke, a lifetime engine warranty was offered. It was a gimmick, Millet admits, good only for as long as the original owner on the car – later extended to the second owner. The V-4, however, was inevitable and sales in the U.S. ended.

Off the Boat

The first major shipment of Saabs arrived in Boston in December 1956 and, as they say, if it had been a movie no one would believe it. U.S. Customs demanded the cars be removed from the port immediately, and Millet’s assembled team of college students, mostly from Boston University, obliged a little too well. Reports had cars racing three abreast and drivers otherwise enjoying themselves, at least until a crash substantially damaged two cars, fortunately with no injuries. This was – after the fire department had been called out when all the Saabs, their engines smokier than usual, having been preserved in Sweden before shipping by pouring oil down the carburetor – raised such a cloud of smoke someone pulled the fire alarm. Reportedly, Customs was enraged, the fire department peeved, and there was the general bedlam caused by the student drivers. At least it had the longshoreman rolling with laughter. All cars were in Hingham, Massachusetts, by midnight, ready to be prepped for shipment to dealers, but apparently it was for all a day to remember.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.