Originally published in AutoWeek, April 25, 1988.

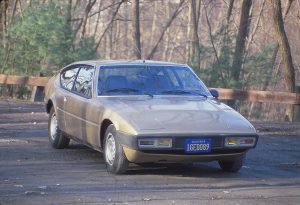

1965 Matra-Bonnet Djet, photos by John Matras.

Europa. Miura. Manguta. Dino. Stratos. Pantera. Countach. Boxer. Bora. Esprit. M1. 308. Mondial. Testarossa. GTO.

Compile a list of favorite enthusiast cars and often as not you’ll find the engine is in the middle. Excuses are low polar moment, front-to-rear balance, responsive handling, and superior traction for acceleration and braking. And anyway, when John Cooper’s mid-engine F2 cars swept the racing world in 1957, it was only a matter of time before the public was persuaded mid-engine was the ultimate configuration.

Ironically, the usual list of mid-engine road cars overlooks the one that started it all. The first modern production automobile with the engine located behind the driver and in front of the rear axle was the Rene-Bonnet Djet.

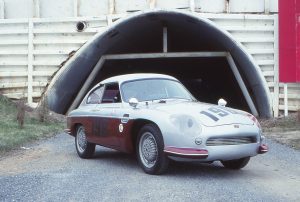

The Djet was the brainchild of its namesake, Frenchman Rene Bonnet, who ended his handshake partnership with Charles Deutsch, breaking up DB (Deutsch-Bonnet), and formed his own automobile company in 1961. The Djet debuted in competition form at the 1962 Nurburgring 1000 Kilomaters, followed by a second in the Index of Performance at LeMans in 1963.

The road-going Djet, introduced in 1963, differed little from the racer. Built on a tube chassis, it had fully independent suspension and four-wheel Lockheed disc brakes. The engine was from Renault, 1108 cc, in either 65 or 80 hp form, or a 100 horse 996 cc dohc twin-Weber version was available for racing. Set longitudinally in the chassis, it powered the rear wheels through a Renault four-speed transmission. The radiator was in the nose. Over all of this was a fiberglass body of a piscine French profile, peculiar but aerodynamic as top speed was 100 mile-per-hour even with the 65 horse engine.

Only about 190 the Rene-Bonnet DJets were built; not enough to keep the wolf from the door. Bonnet had begun his company largely on loan from Marcel Chassagny, founder and then head of the French aerospace firm Matras. It was inevitable that Matra would step in to protect its investment, and in September 1964 the immodestly named marque Rene-Bonnet ceased to exist. In its place was Matra-Bonnet.

The Djet, however, continued. Two versions were offered, the Djet 5 and that it Djet 5S. Both again had 1108 cc Renault power, the former a 70 hp version with a single Zenith carburetor. The 5S got the Gordini-modified mill. Two big-as-the-engine Solex C.40 PHH twin-throat horizontal carburetors were hung off to one side of the head, and with a special cross-flow hemispherical combustion chamber design, 10.4:1 compression and tube headers, the 5S engine produced 90 HP at 6500 rpm.

Matra-Bonnet lasted for the 1965 model year only, with 1966 production of the Djet prefixed simply by Matra. With even more variations offered, it was the best year ever for the Djet, with 810 made altogether. In 1967 Matra introduced the 530, and although the older model, now called the Jet, outsold it, it was the beginning of the end. Only 17 Jets were built in 1968, and more of the 530 were made that year than all DJets and Jets put together. In the five years of the models existence under all its various names, a total of 1491 were made.

Not surprisingly, Matras are rare in the U.S. Gary Sommers of Monticello, N.Y., has one of the few Matras here, a 1965 Matra-Bonnet Djet. It’s restored to original, including the two-tone red and black paint, but missing the hemispherical hubcaps that came with the car, victims of rust. Favoring originality, Gary has also retained the original ride height and wheels.

It’s said that Rene Bonnet wanted the Djet to be a “people’s car,” much like the VW Beetle, although it approximates more the Karmann-Ghia. If so he could hardly have missed his mark more widely. The Djet has the soul of a kit car. Many details are insufficiently thought out, the kind of errors of too few minds working on too big a problem. Gary removed the front bumper, for example, because it was so poorly supported it shook, cracking the fiberglass around it. Inside, the sun visors won’t clear the rear view mirror no matter how it is turned. Then there are the oddities, such as the choke pull which is on the bulkhead behind the passenger’s right shoulder. There’s nothing wrong with that; it’s within easy reach of the driver. It’s just that it’s, well, different.

The engine lives under a carpeted cover and access to it is actually quite good once you crawl into the luggage compartment under the glass hatchback. And when you are in the luggage compartment working on the engine, there is actually a fair amount of usable space.

Space is typical of cars the size, meaning there’s no room behind the seats and the driver and passenger are an elbow apart. The steering wheel is large, thin-rimmed and horribly vertical, and the shifter has a vagueness earned from its distance from the transmission. As the car weighs less than 1400 pounds, the 1108 cc Gordini engine makes the coupe a brisk performer as long as it holds its tune – which, considering its radical carburetion, can be measured in minutes. Can you imagine a people’s car that recommends warm-up spark plugs? Humble beginnings to be sure and the type of car that Matra had put behind it by the time of the Bagheera, much as Saab had gone beyond the original Sonett. Doubtless others would have “invented” the mid-engine road car had the Djet not come first. Yet the true honor belongs not to the more famous but the first. Perhaps had Rene Bonnet’s business acumen matched his ego and enthusiasm, his slinky little sportster might be better known for the pioneer it was.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.