History originally published in Autoweek February 8, 1988

I had watched the morning mist rise and seen the sun come up, casting first light and shadows over the bulging, primitive shape of a 427 Cobra. I had heard the idle throb of Ford’s 7.0 liter monster motor, the notorious NASCAR side-oiler. I had felt it unfold its relentless, overwhelming strength. I had held lightning in my own hands: Now I know how a god feels.

Anyone who has even the most passing knowledge of the automobile knows the Cobra. They may not know who Carroll Shelby is and how he saved AC Cars Ltd. from possible extinction when he suggested mating a “Ford Fairlane V-8” with AC’s Ace. They may not know that the 289 cu. in. Cobra wrote the Corvette’s dominance of SCCA racing into past tense. But they do know that the Cobra is one of the hottest pieces of automotive equipment to ever leap asphalt and single bounds.

Even faster than a speeding-bullet 289 Cobra, however, was the more-powerful-than-a-locomotive 427. It was Shelby’s response to the Corvette Grand Sport project, his bid to retain control of sports car racing. The first 427 Cobra was an experiment by the late Ken Miles, who stuffed the big Ford V8 into a well-worn 289 chassis and took it to Sebring in 1964. He didn’t finish, the car succumbing to injuries encountered when running down a small tree in practice. But the car was sufficiently impressive to warrant further experimentation.

The original Ace/Cobra suspension front and rear was a lower control arm and a transverse leaf spring that also served as the upper locating link. It was adequate for the 289, but overpowered by the bigger engine. Shelby enlisted Ford suspension expert Klaus Arning to make the transformation, which started with a stronger frame. The tube chassis was increased in wall thickness and grew in tube diameter. The tubes themselves were shoved apart 2 ½ inches to make room for the new engine and the car became five inches wider. The suspension was replaced with proper double A-arms with dimensions determined with help from Ford’s computer. Wheels were then-ultrawide 7.50 inch by 15 Halibrand aluminum; the tires of choice were Goodyear Blue Dot 8.15×15. Bodywork to fit the wider package included wider flares on the fenders and a bigger grill opening for extra cooling.

There were several versions of the 427 Cobra. The first was the racer. These all came with the side-oiler NASCAR 427, so named for the external oil lines necessary for racing lubrication. When it became evident that the production run of 100 cars required for FIA homologation couldn’t be met with pure racers, Shelby created the 427 S/C, for “semicompetition.” These were thin veils of streetability pulled over pure racers: full windscreens, semi-muffled side exhaust, and rubber bushings instead of bronze in the suspension.

These were followed by more civilized editions, with smaller fenders and fuel tank but still the 427 engine. Then some Dearborn bean-counter noticed that a Ford Police Interceptor 428 engine cost $320 versus $730 for the NASCAR 7.0 liter and a whole string of Cobras came with the slightly less powerful motor. Only after May 1967 did the genuine 427 become available again, though not as the S/C. The numbers are two prototype competition roadsters, 19 production roadsters, 30 S/Cs, 260 street cars, one Daytona super coupe, three uncompleted chassis, and 32 AC 289’s, coil sprung cars with the smaller Ford V8 sold by AC mostly in England and Europe. Production ended when it became evident that there was simply no way the Cobra could ever meet the 1968 federal safety regulations.

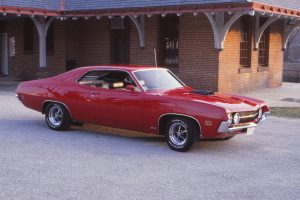

It was one of the ‘66 street 427’s that I had spent time with, #SX3354, newly restored by Jeff Howard of Connecticut and belonging to Steve Pagano of Voorhees, New Jersey. Though not perhaps as brutal as the race or S/C 427’s, it still possessed stunning power. Autumn leaves and morning dew on the roads through the South Jersey Pine Barrens called for maximum trepidation and respect, but when the sun-dried sections presented themselves, I was able to confirm every rumor and tale ever told about Ol’ Shel’s snake.

Just stand on the throttle – no tricks with the clutch, no worry about what gear – and the rear end gets loose, the tires spin. You’d swear it was a slipping clutch. But it isn’t. And anyway the car is bounding ahead and it’s time for another gear and, by Zeus, it will do it again.

All this is done with the driver in the most peculiar of positions. Because the lump under the hood is so big and so far back, the foot well is skewed to the left and the driver has to point his lower torso somewhere towards the next Lane over. The shift lever exits the tunnel about the driver’s elbow and runs forward at about a 45-degree angle. The shifter is effectively grasped from behind and moved in a vertical pattern, sort of like a backwards Alfa. It sounds awkward, but it’s really easily accommodated. Not so easily live with, however, are the pedals. Individuals with normal appendages need not try to heel-and-toe. The easy answer is that it wasn’t necessary: John Wayne never dance ballet.

The most surprising aspect of the 427 Cobra, however is this docility in traffic. It’s sort of like learning Arnold Schwarzenegger is a simple homebody at heart. The Cobra sits calmly at a traffic light – it owns at least the next quarter mile, for gosh sakes – and will trundle around behind Pintos and pickup trucks, content with the small primary bores of the ultimately massive four barrel Holley carburetor. Even the ride is relatively smooth. They say that if you stay around long it enough the engine turns the fiberglass foot wells into ovens, however.

Only the powerful need not make ostentatious display of power. The 427 Cobra makes a driver feel like a god. When your quiver’s full of thunderbolts, you’re in for an almighty drive.

What Do You Think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.