History/driving impressions originally published in AutoWeek August 9, 1982

Do something, I thought. But no, the Jensen FF belied its four-wheel-drive and behaved like a normal car. A very nice normal car, to be sure, but still a normal car.

There is the subdued but omnipresent throb of the common Chrysler 383 V-8, barely audible at idle but a mellow bellow at full throttle. The 330 horses pull strongly and acceleration is good, the engine’s torque leaning against a rather longish final drive ratio.

Handling is remarkable more for the lack of remarkableness than anything else. The ride is firm but comfortable, and cornering is accomplished on an even keel. The rack-and-pinion steering, although obviously power-assisted, feels precise and offers excellent road feedback.

But from a seat-of-the-pants standpoint, there is precious little to indicate that the Jensen FF is in its own way one of the most exotic of the exotics. Not, of course, in regards to the power plant. The Pentastar power plant powered a plethora of Plymouths on nothing more romantic than a speed run to the local A&P. Nor for the conventional coil-spring/A-arm front and live-axle-on-leafs/Panhard-rod rear suspension. Not even the handsome Vignale-designed body over a tubular chassis structure rates the ultra-exotic label. What does earn the FF place on motoring’s Mount Olympus are its drivetrain and braking system. Normally these items are footnotes in an automobile specifications, but not when they are Ferguson four-wheel-drive and Dunlop Maxaret anti–skid braking systems. The Ferguson system is an ingenious solution to the problem of applying power to all four wheels on a full-time basis on a road-going automobile.

Without going into micro detail, here’s how it works: Behind the Torqueflite three speed automatic, a unit resembling an overdrive with the power take-off is mounted. Inside this assembly of castings is a planetary master differential which allows speed differences between the front and rear axles. The rear output shaft comes directly out of the back of the unit, while a chain drive out to the side connects the front output shaft. A pair of one-way clutches operating off slightly different sized gears on the input shaft “senses” mechanically which axle is turning faster by preselected amount (indicating tires slipping), and transmit the power to the other end. In the FF, the front axle may over speed by 16.5%, the rear axle by 5.5%, before the one-way clutch solidifies. The planetary master differential allows different torque to be applied to either end, in this case 37% to the front and an 83% to the rear, at least until the tires on one end start slipping and one-way clutches take over.

With the front output shaft forward alongside the engine, the Jensen FF can sit lower in proper sports sedan fashion. But the half-shafts running off to the front differential must do so in front of the engine instead of underneath.

However, the engine sets well back in the FF’s two-wheel-drive sibling, the Interceptor, and the FF is only 4 inches longer to fit the four-wheel-drive mechanisms. The additional length is in between the front axle and the cowl, and this shows in the double side vents. The interceptor has a single vent. (Jensen spotters take note!)

The Maxaret anti-skid braking unit runs off the Ferguson drive, sensing impending lockup by comparing drivetrain “speed” and individual wheel speed, momentarily releasing brake line pressure to any wheel starting to skid.

Still, very little of this sophistication could be felt in normal driving. It did show up, in a negative sort of way, with the steering at full lock. The tires could be felt “crabbing” as power was applied. A more positive display came when we tried to get some dust and gravel throwing photos. No matter what car owner Ben Fishel did, the car refused to sling gravel for the camera. It just dug in and motored away. Admittedly it was hard-packed gravel, and the long axle ratio works against such foolishness, but even loading the torque converter against the brakes wouldn’t break the tires loose.

One final test: With one side of the car on the road and the other on the gravel shoulder, I hit the brakes. The result was astounding. The car just stopped, and in a straight line. Only the left front wheel – the one on the asphalt – locked up, and that just before the car came to a complete halt. Impressive.

One other impression came through, and that was the mechanical drag in the system. It’s not apparent at first because the sensation is that of engine braking with a standard transmission. But the FF has an automatic, and ought to be able to practically coast in high. If it slows the car that much on closed throttle, it must be a real horse thief and gas guzzler.

Jensen didn’t flood the world with FFs. The car carried of $4,000 tariff over the Interceptor’s price tag of $10,000, and that in 1967. At 3,800 pounds, it carried a penalty of 300 pounds over its two-wheel-drive twin, making it slower than the Interceptor under most conditions – especially when the Interceptor began receiving Chrysler’s big 440. And it was essentially a two-seater. The sumptuous double barrel-backed rear seat has no legroom. Nor was it ever officially imported into the US.

The FF would seem to be a natural for rallying, but conversions of more modern chassis to the Ferguson systems haven’t been setting the woods afire. No, the FF was not a racer. It was a gentleman’s express, a “personal car” of the first order. It was perfect for the individual with a lot of money and somewhere else to be, regardless of the weather or road on the way. Really, James Bond should’ve turned in the Aston Martin for one of these: “The Red Guard closed all the roads out of China? Don’t you worry, my dear, we shall merely detour over the Himalayas on a yak path known only to four Sherpas and myself.”

I wonder if an ejection seat could be fitted? Does MI-5 know about this?

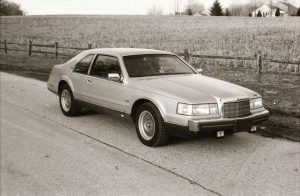

Over the 40 year period, some things have gone amiss, and that includes the negatives for the photos of this Jensen FF. I therefore copied and gently massaged the newsprint halftone from AutoWeek, then still printed on newsprint and in tabloid size.

Terminology changes: Common usage today for a full-time system like the Furguson is all-wheel drive. Four-wheel driveis used for part-time systems that drive two wheels, usually the rear, until shifted into four-wheel operation. Another change in usage is saying “anti-lock” braking rather than the almost quaint “anti-slip.”

What Do You Think?